Somatic Symptom Disorder could capture millions more under mental health diagnosis

May 26, 2012

Somatic Symptom Disorder could capture millions more under mental health diagnosis

Post #172 Shortlink: http://wp.me/pKrrB-29B

By Suzy Chapman | Dx Revision Watch

Update: My submission to the Somatic Symptom Disorder Work Group in response to the third DSM-5 draft and stakeholder review can be read here: Chapman Response to Third Draft DSM-5 SSD Proposals

May 26, 2012

While media and professional attention has been focused on the implications for introducing new disorders into the DSM and lowering diagnostic thresholds for existing categories, the Somatic Symptom Disorders (SSD) Work Group has been quietly redefining DSM’s Somatoform Disorders with radical proposals that could bring millions more patients under a mental health diagnosis.

The SSD Work Group is proposing to rename the Somatoform Disorders section of DSM-IV to “Somatic Symptom Disorders,” eliminate four existing DSM-IV categories: somatization disorder [300.81], hypochondriasis [300.7], pain disorder*, and undifferentiated somatoform disorder [300.82] and replace them with a single new category – “Somatic Symptom Disorder.”

*In DSM-IV: Pain Disorder associated with a general medical condition (only): Psychological factors, if present, are judged to play no more than a minimal role. This is not considered a mental disorder so it is coded on Axis III with general medical conditions.See http://behavenet.com/pain-disorder for definitions and criteria for other DSM-IV presentations of Pain disorder. For DSM-5, it appears that all presentations of Pain disorder will be subsumed under the new SSD category.

If approved, these proposals will license the application of a mental health diagnosis for all illnesses – whether “established general medical conditions or disorders” like diabetes, heart disease and cancer or conditions presenting with “somatic symptoms of unclear etiology” – if the clinician considers the patient is devoting too much time to their symptoms and that their life has become “subsumed” by health concerns and preoccupations, or their response to distressing somatic symptoms is “excessive” or “disproportionate,” or their coping strategies “maladaptive.”

Somatoform Disorders – disliked and dysfunctional

The SSD Work Group, under Chair, Joel E. Dimsdale, MD, says current terminology for the Somatoform Disorders is confusing and flawed; that no-one likes these disorders and they are rarely used in clinical psychiatric practice. Primary Care physicians don’t understand the terms and patients find them demeaning and offensive [1,2].

The group says the terms foster mind/body dualism; that the concept of “medically unexplained” is unreliable, especially in the presence of medical illness, and cites high prevalence of presentation with “medically unexplained somatic symptoms” (MUS) in general medical settings – 20% in Primary Care, 40% in Specialist Care, 33-61% in Neurology; that basing a diagnosis of psychiatric disorder on MUS alone is too sensitive.

The Work Group might have considered dispensing altogether with a clutch of disliked, dysfunctional categories. Instead, the group proposes to rebrand these disorders and assign new criteria that will capture patients with diverse illnesses, expanding application of psychiatric services, antidepressants and behavioural therapies like CBT, for the “modification of dysfunctional and maladaptive beliefs about symptoms and disease, and behavioral techniques to alter illness and sick role behaviors.”

Focus shifts from “medically unexplained” to “excessive thoughts, behaviors and feelings”

The Work Group’s proposal is to deemphasize “medically unexplained” as the central defining feature of this disorder group.

For DSM-5, focus shifts to the patient’s cognitions – “excessive thoughts, behaviors and feelings” about the seriousness of distressing and persistent somatic (bodily) symptoms – which may or may not accompany diagnosed general medical conditions – and the extent to which “illness preoccupation” is perceived to “dominate” or “subsume” the patient’s life.

“[The SSD Work Group’s] framework will allow a diagnosis of somatic symptom disorder in addition to a general medical condition, whether the latter is a well-recognized organic disease or a functional somatic syndrome such as irritable bowel syndrome or chronic fatigue syndrome…” [3]

“…These disorders typically present first in non-psychiatric settings and somatic symptom disorders can accompany diverse general medical as well as psychiatric diagnoses. Having somatic symptoms of unclear etiology is not in itself sufficient to make this diagnosis. Some patients, for instance with irritable bowel syndrome or fibromyalgia would not necessarily qualify for a somatic symptom disorder diagnosis. Conversely, having somatic symptoms of an established disorder (e.g. diabetes) does not exclude these diagnoses if the criteria are otherwise met…” [4]

To meet requirements for Somatization Disorder (300.81) in DSM-IV, a considerably more rigorous criteria set needed to be fulfilled: a history of many medically unexplained symptoms before the age of thirty, resulting in treatment sought or psychosocial impairment. The diagnostic threshold was set high – a total of eight or more medically unexplained symptoms from four, specified symptom groups, with at least four pain and two gastrointestinal symptoms.

In DSM-5, the requirement for eight symptoms is dropped to just one.

One distressing symptom for at least six months duration and one “B type” cognition is all that is required to tick the box for a bolt-on diagnosis of a mental health disorder – cancer + SSD; angina + SSD; diabetes + SSD; IBS + SSD…

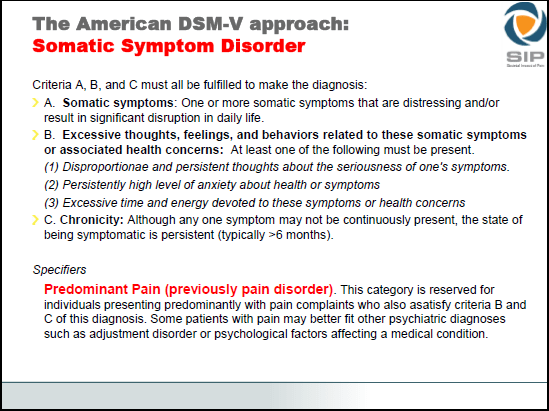

The most recent proposals for new category “J 00 Somatic Symptom Disorder.”

Note that the requirement for “at least two from the B type criteria” for the second draft has been reduced to “at least one from the B type criteria” for the third iteration of draft proposals. This lowering of the threshold is presumably in order to accommodate the merging of the previously proposed “Simple Somatic Symptom Disorder” category into the “Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder” category, a conflation now proposed to be renamed to “Somatic Symptom Disorder.” No revised “Disorder Description” and “Rationale/Validity” documents reflecting the changes made between draft two and draft three were issued for the third and final draft.

Ed: Update: Following closure of the third stakeholder review on June 15, 2012, proposals, criteria and rationales were frozen and the DSM-5 Development website was not updated to reflect any subsequent revisions. Proposals, criteria and rationales, as posted for the third draft in May 2012, were removed from the DSM-5 Development website on November 15, 2012 and placed behind a non public log in. Consequently, criteria as they had stood for “Somatic Symptom Disorder” at the point at which the third draft was issued can no longer be accessed but are set out on Slide 9 in this presentation, which note, does not include three, optional Severity Specifiers that were included with the third draft criteria. Since any changes to the drafts are embargoed in preparation for publication of DSM-5, in May 2013, I cannot confirm whether any changes have been made to the draft subsequent to June 15, 2012.

IASP and the Classification of Pain in ICD-11 Prof. Dr. Winfried Rief, University of Marburg, Germany

Slide 9

How are highly subjective and difficult to measure constructs like “Disproportionate and persistent thoughts about the seriousness of one’s symptoms” and “Excessive time and energy devoted to these symptoms or health concerns” to be operationalized?

By what means would a practitioner determine how much of a patient’s day spent “searching the internet looking for data” (to quote an example of the SSD Work Group Chair) might be considered a reasonable response to chronic health concerns and what should be coded as “excessive preoccupation” or indicate that this patient’s life has become “subsumed” or “overwhelmed” by concerns about illness and symptoms? One hour day? Two hours? Three?

At the APA’s Annual Conference earlier this month, SSD Work Group Chair, Joel E. Dimsdale, presented an update on his group’s deliberations. During the Q & A session, an academic professional in the field expressed concern that practitioners who are not psychiatric professionals or clinicians might have some difficulty interpreting the wording of the B type criteria to differentiate between negative and positive coping strategies.

Dr Dimsdale was asked to expand on how the B type criteria would be defined and by what means patients with chronic medical conditions who devote time and energy to health care strategies to try to improve their symptoms and level of functioning would be evaluated in the field by the very wide range of DSM users; how would these patients be differentiated from patients considered to be spending “excessive time and energy devoted to symptoms or health concerns” or perceived as having become “absorbed” by their illness?

I am not persuaded by Dr Dimsdale’s reassurances that his Work Group will try to make this “crystal clear” in the five to six pages of manual text in the process of being drafted for this disorder chapter. Nor am I reassured that these B (1), (2) and (3) criteria can be safely applied outside the optimal conditions of field trials, in settings where practitioners may not necessarily have the time for, nor instruction in administration of diagnostic assessment tools, and where decisions to code or not to code may hang on arbitrary and subjective perceptions of DSM end-users lacking clinical training in the use of the manual text and application of criteria.

Implications for a diagnosis of SSD for all patient populations

Incautious, inept application of criteria resulting in a “bolt-on” psychiatric diagnosis of a “Somatic Symptom Disorder” could have far-reaching implications for all patient populations:

• Application of highly subjective and difficult to measure criteria could potentially result in misdiagnosis with a mental health disorder, misapplication of an additional diagnosis of a mental health disorder or missed diagnoses through dismissal and failure to investigate new or worsening somatic symptoms.

• Patients with cancer and life threatening diseases may be reluctant to report new symptoms that might be early indicators of local recurrence, metastasis or secondary disease, for fear of attracting a diagnosis of “SSD” or of being labelled as “catastrophisers.”

• Application of an additional diagnosis of Somatic Symptom Disorder may have implications for the types of medical investigations, tests and treatments that clinicians are prepared to consider and which insurers prepared to fund.

• Application of an additional diagnosis of Somatic Symptom Disorder may impact payment of employment, medical and disability insurance and the length of time for which insurers are prepared to pay out. It may negatively influence the perceptions of agencies involved with the assessment and provision of social care, disability adaptations, education and workplace accommodations.

• Patients prescribed psychotropic drugs for perceived unreasonable levels of “illness worry” or “excessive preoccupation with symptoms” may be placed at risk of iatrogenic disease or subjected to inappropriate behavioural therapies.

• For multi-system diseases like Multiple Sclerosis, Behçet’s syndrome or Systemic lupus it can take several years before a diagnosis is arrived at. In the meantime, patients with chronic, multiple somatic symptoms who are still waiting for a diagnosis would be vulnerable.

• The burden of the DSM-5 changes will fall particularly heavily upon women who are more likely to be casually dismissed when presenting with physical symptoms and more likely to receive inappropriate antidepressants and anti-anxiety medications for them.

• Proposals allow for the application of a diagnosis of Somatic Symptom Disorder where a parent is considered excessively concerned with a child’s symptoms [3]. Families caring for children with any chronic illness may be placed at increased risk of wrongful accusation of “over-involvement” with a child’s symptomatology.

Where a parent is perceived as encouraging maintenance of “sick role behaviour” in a child, this may provoke social services investigation or court intervention for removal of a sick child out of the home environment and into foster care or for enforced in-patient “rehabilitation.” This is already happening in families with a child or young person with chronic illness, notably with Chronic fatigue syndrome or ME. It may happen more frequently with a diagnosis of a chronic childhood illness + SSD.

Dustbin diagnosis?

Although the Work Group is not proposing to classify Chronic fatigue syndrome, IBS and fibromyalgia, per se, within the Somatic Symptom Disorders, patients with CFS – “almost a poster child for medically unexplained symptoms as a diagnosis,” according to Dr Dimsdale’s presentation – or with fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, chronic Lyme disease, Gulf War illness, chemical injury and chemical sensitivity may be particularly vulnerable to misapplication or misdiagnosis with a mental health disorder under these SSD criteria.

There is considerable concern that this new Somatic Symptom Disorder category will provide a “dustbin diagnosis” in which to shovel the so-called “functional somatic syndromes.”

15% of “diagnosed illness” and 26% of “functional somatic” captured by SSD criteria

For testing reliability of CSSD criteria, three groups were studied for the field trials:

488 healthy patients; a “diagnosed illness” group of 205 patients with cancer and malignancy (some in this group were said to have severe coronary disease) and a “functional somatic” group comprising 94 people with irritable bowel and “chronic widespread pain” (a term used synonymously with fibromyalgia).

Patients in the study were required to meet one to three cognitions: Do you often worry about the possibility that you have a serious illness? Do you have the feeling that people are not taking your illness seriously enough? Is it hard for you to forget about yourself and think about all sorts of other things?

Dr Dimsdale reports that if the response was “Yes – a lot.” then [CSSD] was coded.

15% of the cancer and malignancy group met SSD criteria when “one of the B type criteria” was required; if the threshold was increased to “two B type criteria” about 10% met criteria for dual-diagnosis of diagnosed illness + Somatic Symptom Disorder.

For the 94 irritable bowel and “chronic widespread pain” study group, about 26% were coded when one cognition was required; 13% coded with two cognitions required.

Has the SSD Work Group produced projections for prevalence estimates and potential increase in mental health diagnoses across the entire disease landscape?

Did the Work Group seek opinion on the medico-legal implications of missed diagnoses?

Has the group factored for the clinical and economic burden of providing CBT for modifying perceived “dysfunctional and maladaptive beliefs about symptoms and disease, and behavioral techniques to alter illness and sick role behaviors” in patients for whom an additional diagnosis of Somatic Symptom Disorder has been coded?

Where’s the science?

Dr Dimsdale admits his committee has struggled from the outset with these B type criteria but feels its proposals are “a step in the right direction.”

The group reports that preliminary analysis of field trial results shows “good reliability between clinicians and good agreement between clinician rated and patient rated severity.” In the trials, CSSD achieved Kappa values of .60 (.41-.78 Confidence Interval).

Kappa reliability reflects agreement in rating by two different clinicians corrected for chance agreement – it does not mean that what they have agreed upon are valid constructs.

Radical change to the status quo needs grounding in scientifically validated constructs and a body of rigorous studies not on pet theories and papers (in some cases unpublished papers) generated by Dr Dimsdale’s work group colleagues.

Where is the substantial body of independent research evidence to support the group’s proposals?

“...To receive a diagnosis of complex somatic symptom disorder, patients must complain of at least one somatic symptom that is distressing and/or disruptive of their daily lives. Also, patients must have at least two [Ed: now reduced to at least one since evaluation of the CSSD field trials] of the following emotional/cognitive/behavioral disturbances: high levels of health anxiety, disproportionate and persistent concerns about the medical seriousness of the symptom(s), and an excessive amount of time and energy devoted to the symptoms and health concerns. Finally, the symptoms and related concerns must have lasted for at least six months.”

“Future research will examine the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, or treatment of complex somatic symptom disorder as there is no published research on this diagnostic category.”

“…Just as for complex somatic symptom disorder, there is no published research on the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, or treatment of simple somatic symptom disorder.”

Source: Woolfolk RL, Allen LA. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Somatoform Disorders. Standard and Innovative Strategies in Cognitive Behavior Therapy.

Where are the professionals?

During the second public review, the Somatic Symptom Disorders proposals attracted more responses than almost any other category. The SSD Work Group is aware that patients, caregivers and patient advocacy organizations have considerable concerns. But are medical and allied health professionals scrutinizing these proposals?

This is the last opportunity to submit feedback. Psychiatric and non psychiatric clinicians, primary care practitioners and specialists, allied health professionals, psychologists, counselors, social workers, lawyers, patient advocacy organizations – please look very hard at these proposals, consider their safety and the implications for an additional diagnosis of an SSD for all patient illness groups and weigh in with your comments by June 15.

Criteria and rationales for the third iteration of proposals for the DSM-5 Somatic Symptom Disorders categories can be found here on the DSM-5 Development site. [Update: Proposals were removed from the DSM-5 Development website on November 15, 2012.]

References

1 Levenson JL. The Somatoform Disorders: 6 Characters in Search of an Author. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011 Sep;34(3):515-24.

2 Dimsdale JE. Medically Unexplained Symptoms: A Treacherous Foundation for Somatoform Disorders? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011 Sep;34(3):511-3.

3 Dimsdale J, Creed F. DSM-V Workgroup on Somatic Symptom Disorders: the proposed diagnosis of somatic symptom disorders in DSM-V to replace somatoform disorders in DSM-IV – a preliminary report. J Psychosom Res 2009;66:473–6.

4 DSM-5 Somatic Symptom Disorders Work Group Disorder Descriptions and Justification of Criteria-Somatic Symptoms documents, published May 4, 2011 for the second DSM-5 stakeholder review.

(Caveat: for background to the SSD Work Group’s rationales only; proposals and criteria as set out in these documents have not been revised to reflect changes to revisions or reissued for the third review.)

![]() Disorder Descriptions May 4, 2011

Disorder Descriptions May 4, 2011

![]() Rationale/Validity Document May 4, 2011

Rationale/Validity Document May 4, 2011