June 20, 2015

by admindxrw

There are two ways in which stakeholders can submit comments on proposals in the ICD-11 Beta draft or make formal suggestions for changes or additions to the draft:

• by selecting a disorder or disease term and submitting a comment on the proposed ICD-11 Title term, on the proposed Definition text (if a Definition has already been populated), or commenting on the lists of Synonyms, Inclusions, Exclusions or on any other Content Model descriptors. Users may also leave replies to comments submitted by other users or invite others to participate in threads;

• by selecting a disorder or disease term and suggesting changes to the classification or enhancement of existing content by proposing Definition texts, additional Synonyms or Exclusions, additional child entities, changes to existing parent/child hierarchies or deletions of existing entities – ideally supported with rationales and references. Proposals for changes or suggestions for modifications are submitted via the Proposals Mechanism platform. This platform also supports user comments. Once submitted, the progress of a proposal can be tracked.

To register for interaction with the Beta draft see User Guide: Information on registering and signing in

To comment on existing proposals see User Guide: Commenting on the category

To suggest changes or submit new proposals see User Guide: Proposals

At the time of writing, the Beta draft is subject to a frozen release (frozen May 31, 2015) but this does not prevent registered users from continuing to commenting on the ICD-11 Beta draft or from submitting proposals via the Proposals Mechanism.

Comment submitted to TAG Mental Health in May re: Bodily distress disorder

On May 2, 2015, I posted a commentary via the ICD-11 Beta platform Comment facility. As one needs to be registered in order to read/make comments and submit proposals, I have pasted a copy, below.

Once uploaded, Comments and Proposals are screened and forwarded to the appropriate Topic Advisory Group (TAG) Managing Editors for their consideration. In this case, my comment will have been forwarded to the Topic Advisory Group for Mental Health.

Some of the points raised, below, had already been raised by me, either via the Beta platform or directly with ICD Revision personnel. But it may be advantageous to consolidate these points within the one comment for two reasons:

Firstly, the level of global concern around ICD-11 proposals by the WHO ICD-11 Working Group on Somatic Distress and Dissociative Disorders for a new disorder construct, currently proposed to be called “Bodily distress disorder (BDD),” and also for the alternative proposals of the ICD-11 Primary Care Consultation Group.

Secondly, the unsoundness of introducing into ICD a new disorder category that proposes to use terminology which is already closely associated with a conceptually divergent disorder construct isn’t being given due attention in journal papers or editorials and has yet to be acknowledged or addressed by the ICD-11 subworking group responsible for this recommendation.

Chapman BDD Submission May 2015

Chapman BDD Submission May 2015

Comment, Bodily distress disorder

http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/767044268?showcomment=_4_id_3_who_3_int_1_icd_1_entity_1_767044268 [Log in required]

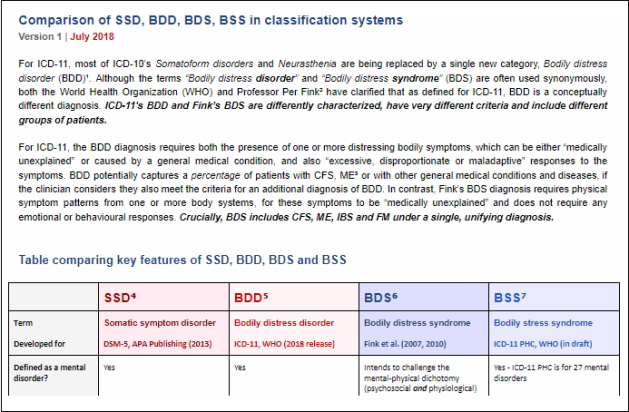

It should be noted that earlier this year, TAG Mental Health added the new DSM-5 disorder term “Somatic symptom disorder” under Synonyms to “Bodily distress disorder (BDD).”

I welcome affirmation that BDD, as defined by ICD-11 Beta, shares common conceptual features with DSM-5’s SSD.

However, as with “Somatic symptom disorder”, the proposed “Bodily distress disorder” diagnosis is unsupported by any substantial body of evidence for its likely validity, safety and acceptability. We [Allen Frances and Suzy Chapman, 2012-13] have called for a higher standard of evidence and risk-benefit analysis for ICD Revision [1][2][3].

BDD’s characterization, as entered into the Beta draft and as described by Gureje and Creed (2012), is far looser than the (rarely used) definitions of Somatization disorder in DSM-IV and in ICD-10 [4].

BDD broadens the diagnosis to include those where a diagnosed general medical condition is causing or contributing to the symptom(s) if the degree of attention is considered excessive in relation to the condition’s nature and progression. Like SSD, the diagnosis does not require symptoms to be “medically unexplained” but instead refers to any persistent and clinically significant somatic complaint(s) with associated psychobehavioural responses: excessive thoughts, feelings and behaviours. There were long-standing concerns for the over-inclusiveness of DSM-IV’s Undifferentiated somatoform disorder.

BDD’s three severity specifiers rely on highly subjective clinical decision making around loose and difficult to measure cognitions; as with SSD, there are considerable concerns that lack of specificity will expose patients to risk of misdiagnosis, missed or delayed diagnosis, misapplication of a mental disorder, iatrogenic disease and stigma.

Whether the term “Bodily distress disorder” (or “Body distress disorder,” as Sudhir Hebbar [a psychiatrist who had left an earlier comment on the Beta draft in respect of the proposed BDD name and disorder construct] has suggested) is used for this proposed replacement for the Somatoform disorder categories, F45.0 – F45.9, plus F48.0 Neurasthenia, both the disorder conceptualization and the terminology remain problematic.

The terms “Bodily distress disorder” and “Bodily distress syndrome” (Fink et al, 2010) are already being used synonymously in the literature.

The terms are used interchangeably in papers by Fink and colleagues from around 2007 onwards [5] and by Creed, Guthrie et al, in 2010 [6]. They are used interchangeably by Professor Creed in symposia presentations.

In a September 2014 editorial by Rief and Isaac [7] the term “Bodily distress disorder” has been employed throughout, whereas the construct that Rief and Isaac are actually discussing is the Fink et al (2010) BDS disorder construct – not the “BDD” construct, as defined in the Beta draft – which the authors do not discuss, at all.

According to the Beta draft Definition and BDD’s three severity characterizations (Mild; Moderate; Severe), the WHO ICD-11 Working Group on Somatic Distress and Dissociative Disorders (the S3DWG) defines “Bodily distress disorder” as having strong construct congruency and characterization alignment with DSM-5’s “Somatic Symptom Disorder” and poor conceptual alignment with Fink et al’s, already operationalized, “Bodily distress syndrome” [8].

If, in the context of ICD-11 usage, the S3DWG’s proposal for a replacement for the Somatoform disorders remains for a disorder model with greater conceptual concordance with the DSM-5 SSD construct there can be no rationale for proposing to name this disorder “Bodily distress disorder.”

There is significant potential for confusion over disorder conceptualization and for disorder conflation if the S3DWG’s proposed replacement for the Somatoform disorders has greater conceptual alignment with the SSD construct but is assigned a disorder name that sounds very similar to, and is already being used interchangeably with an operationalized, but divergent construct and criteria set.

Additionally, the acronym “BDD” is already in use to indicate Body Dysmorphic Disorder.

If ICD-11 intends to proceed with the BDD construct following field test evaluation, and despite the lack of a body of evidence for validity, safety and acceptability, then an alternative disorder term needs to be assigned.

In a 2010 paper, Creed and co-authors advanced that “Somatic symptom disorder is not a term that is likely to be embraced enthusiastically by doctors or patients; it has an uncertain core concept, dubious wide acceptability across cultures and does not promote multidisciplinary treatment” and they expressed a preference for the term, “bodily distress syndrome/disorder” [6].

I have no evidence that Prof Creed has changed his opinions about SSD since the publication of DSM-5 and perhaps he remains wedded to the “Bodily distress disorder” term (and wedded to the BDS construct) and is reluctant to relinquish the term.

Creed, Henningsen and Fink acknowledge that Fink et al’s (2010) BDS construct is very different to DSM-5’s SSD; that BDS and SSD have very different criteria and that they capture, or potentially capture, different patient populations [9].

Budtz-Lilly, Fink et al (In Press) outline some of the conceptual differences between SSD and BDS:

“The newly introduced DSM-5 diagnosis, somatic symptom disorder (SSD), has replaced most of the DSM-IV somatoform disorder subcategories [10]. The diagnosis requires the presence of one or more bothering somatic symptoms of any aetiology and is not based on exclusion of any medical condition (…) BDS and SSD represent two very conceptually different diagnoses. BDS is based on symptom pattern recognition only, and symptoms are thought to be caused by hyperactivity in the central nervous system, whereas SSD criteria are based on prominent positive psycho-behavioural symptoms or characteristics, but no hypothesis of aetiology. BDS is assessed without asking patients about psychological symptoms.” [10]

In order to fulfill the clinical criteria of BDS, the symptom pattern may not be better explained by another disease. Whereas the SSD diagnosis may be applied to a heterogeneous group of patients: as a “bolt-on” mental health diagnosis for patients with, for example, cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic pain conditions, or to patients with so-called specialty-specific functional somatic syndromes, or to patients with “functional symptoms”, if the criteria are otherwise met.

SSD, then, clearly cannot be BDS. And if the S3DWG’s BDD is close in conceptualization and criteria to SSD, then the S3DWG’s BDD cannot be BDS, either. But the terms BDD and BDS are already used interchangeably outside ICD-11.

What is the S3DWG rationale for proposing to use this disorder term when the group is aware that outside the context of ICD-11 Beta proposals, the term is synonymously used with an already operationalized, but divergent disorder construct?

Whatever the group’s justification, the term is clearly inappropriate; it needs urgent scrutiny beyond the S3DWG group and I call on TAG Mental Health and the Revision Steering Group to review the BDD disorder descriptions in the context of the group’s current choice of terminology.

But the waters get even muddier:

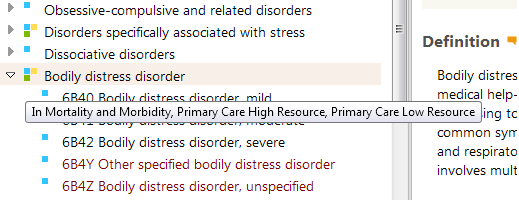

Possibly Sudhir Hebbar and other users of the Beta platform are unaware that in addition to the 17 member S3DWG subworking group’s proposals, the 12 member Primary Care Consultation Group (PCCG) is also charged with advising ICD-11 on the revision of the ICD-10 Somatoform disorders framework and disorder categories.

The 28 mental disorders approved for inclusion in the abridged ICD-11 primary care version will require an equivalent category within the core edition.

The Primary Care Consultation Group [chair, Prof, Sir David Goldberg] has proposed an alternative construct which it proposes to name, “Bodily stress syndrome (BSS)”. The PCCG’s “BSS” draws heavily on the Fink et al (2010) “Bodily distress syndrome” disorder construct and criteria [8][11].

(NB: Rief and Isaac [7] question the justification of the BDS construct for inclusion within a mental disorder classification due to the absence of requirement for positive psychobehavioural features. In 2012, the PCCG’s proposed “BSS” had included some psychobehavioural features to meet the criteria, tacked onto an essentially BDS-like model. Whether this modification was intended as a nod towards DSM-5’s SSD or to legitimise inclusion of a BDS-like model/criteria set within a mental disorder classification is not discussed within the group’s 2012 paper. With no recent update on proposals available, I cannot confirm whether the PCCG’s adapted BDS retains these additional psychobehavioural features.)

Budtz-Lilly, Fink et al (In Press) write:

“In the current draft, the ICD-11 primary care work group has included these [BDS] criteria in their suggestion for a definition of bodily (di)stress syndrome with minor adaptations.” [10] (The paper does not specify what these “minor adaptations” are.)

The authors go on to state:

“Furthermore the ICD-11 somatoform disorder psychiatry work group has announced that the term ‘bodily distress disorder’ will be used for the diagnosis.”

Here, one assumes the authors are referring to the S3DWG subworking group. It is disingenuous of the authors to imply that the S3DWG is onside with the PCCG’s proposals, whilst omitting any discussion of the core differences between the two groups’ proposed disorder constructs and criteria.

According to Ivbijaro and Goldberg (2013) the Primary Care Consultation Group’s (adapted “BDS”) construct has been progressed to field tests [12].

In his September 2014 presentation at the XVI World Congress of Psychiatry, in Madrid, Prof Oye Gureje confirmed that the S3DWG’s “Bodily Distress Disorder” is also currently a subject of tests of its utility and reliability in internet- and clinic-based studies.

So both sets of proposals are undergoing field testing. But since the proposed full disorder descriptions, criteria, differential diagnoses, exclusions etc have not been public domain published and because no progress reports have been issued by either work group since 2012, stakeholders are still unable to scrutinize and compare the two sets of current proposals, side by side.

Significant concerns remain around the deliberations of these two working groups:

a) their lack of transparency: there have been no papers or progress reports published on behalf of either group since 2012; the key Gureje and Creed 2012 paper remains behind a paywall;

b) no rationale has been published for the S3DWG’s proposal to call its proposed construct “BDD” when it evidently has greater conceptual concordance with SSD and poor concordance with Fink et al’s BDS, for which the “BDD” term is already in use, synonymously; there has been no discussion by either group for the implications for construct integrity;

c) it remains unclear whether the S3DWG’s “BDD” will incorporate Exclusions for CFS, ME, Fibromyalgia and IBS, which are currently discretely coded for within ICD-10, and which are considered may be especially vulnerable to misdiagnosis or misapplication of a diagnosis of “BDD”, under the construct as it is currently proposed;

[Dr Geoffrey Reed has said that he cannot request Exclusions until the missing G93.3 legacy terms have been added back into the Beta draft, but at such time, he would be happy to do so.]

d) the PCCG’s “BSS” proposed diagnosis appears to be inclusive of children [11] but there is currently no information from the S3DWG on whether their proposed “BDD” diagnosis is also intended to be applied in children and young people;

e) there is no body of independent evidence for the validity, reliability and safety of the application of “SSD”, “BDD”, “BSS” or Fink et al’s (2010) BDS in children and young people;

f) because of the lack of recent progress reports setting out current iterations for disorder descriptions and criteria, it cannot be determined what modifications and adaptations have been made by the PCCG to the Fink et al (2010) BDS disorder description/criteria for specific ICD-11 field test use. Likewise, the only information to which we have access for the criteria that are being field tested for BDD is what little information appears in the Beta draft.

Fink et al’s BDS construct is considered by its authors to have the ability to capture the somatoform disorders, neurasthenia, noncardiac chest pain and other pain syndromes, “functional symptoms”, and the so-called “FSSs”, including CFS, ME, Fibromyalgia and IBS [8][13].

[Under the Fink et al disorder construct, the various so-called specialty “functional somatic syndromes” are considered to be manifestations of a similar, underlying disorder.]

In Lam et al (2012) the PCCG list a number of diseases and conditions for consideration under Differential diagnosis, vis: “Consider physical disease with multiple symptoms, e.g. multiple sclerosis, hyperparathyroidism, acute intermittent porphyria, myasthenia gravis, AIDS, systemic lupus erythematosus, Lyme disease, connective tissues disease.”

Notably, Chronic fatigue syndrome, ME, IBS and Fibromyalgia are omitted from the Differential diagnosis list. The authors are silent about whether their adapted BDS is intended to capture these discretely coded for ICD-10 diagnoses and if not, how these disorder groups could be reliably excluded [11].

ICD Revision has said that it does not intend to classify CFS, ME and Fibromyalgia under Mental and behavioural disorders. However, it has not clarified what measures would be taken to safeguard these patient groups if BSS were to be approved by the RSG for use in the ICD-11-PHC version.

There have been considerable concerns, globally, amongst patients, patient advocacy groups and the clinicians who advise them for the introduction in Denmark of the BDS disorder construct: these concerns apply equally to “BSS”.

It should also be noted that since early 2013, the ICD-10 G93.3 legacy entities, Postviral fatigue syndrome; Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis; Chronic fatigue syndrome, have been absent from the public version of the Beta draft. For over two years, now, and despite numerous requests (including requests by UK health directorates, parliamentarians and registered advocacy organizations) proposals for the chapter location and parent classes for these three terms (and their proposed Definitions and other Content Model parameters) have not been released.

Again, I request that these terms are restored to the Beta draft, with a “Change History”, in order that professional and lay stakeholders are able to monitor and participate fully in the revision process, a process from which they are currently disenfranchised.

If any clinicians attempting to follow the revision of the Somatoform disorders share concerns for any of the issues raised in these comments and wish to discuss further, they are most welcome to contact me via “Dx Revision Watch.”

References

1 Frances A. The new somatic symptom disorder in DSM-5 risks mislabeling many people as mentally ill. BMJ. 2013 Mar 18;346:f1580.

2 Allen Frances, Suzy Chapman. DSM-5 somatic symptom disorder mislabels medical illness as mental disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013 May;47(5):483-4.

3 Frances A. DSM-5 Somatic Symptom Disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013 Jun;201(6):530-1.

4 Creed F, Gureje O. Emerging themes in the revision of the classification of somatoform disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry 2012;24:556-67.

5 Fink P, Toft T, Hansen MS, Ornbol E, Olesen F. Symptoms and syndromes of bodily distress: an exploratory study of 978 internal medical, neurological, and primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 2007 Jan;69(1):30-9.

6 Creed F, Guthrie E, Fink P et al, Is there a better term than ‘medically unexplained symptoms’?. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:5-8

7 Rief W, Isaac M. The future of somatoform disorders: somatic symptom disorder, bodily distress disorder or functional syndromes? Curr Opin Psychiatry 2014 Sep;27(5):315-9.

8 Fink P, Schroder A. One single diagnosis, bodily distress syndrome, succeeded to capture 10 diagnostic categories of functional somatic syndromes and somatoform disorders. J Psychosom Res. 2010 May;68(5):415-26.

9 Medically Unexplained Symptoms, Somatisation and Bodily Distress: Developing Better Clinical Services, Francis Creed, Peter Henningsen, Per Fink (Eds), Cambridge University Press, 2011.

10 In Press: Anna Budtz-Lilly, Per Fink, Eva Ornbol, Mogens Vestergaard, Grete Moth, Kaj Sparle Christensen, Marianne Rosendal. A new questionnaire to identify bodily distress in primary care: The ‘BDS checklist’. J Psychosom Res. [Published J Psychosom Res. June 2015 Volume 78, Issue 6, Pages 536–545]

11 Lam TP, Goldberg DP, Dowell AC, Fortes S, Mbatia JK, Minhas FA, Klinkman MS: Proposed new diagnoses of anxious depression and bodily stress syndrome in ICD-11-PHC: an international focus group study. Family Practice (2013) 30 (1): 76-87.

12 Ivbijaro G, Goldberg D. Bodily distress syndrome (BDS): the evolution from medically unexplained symptoms (MUS). Ment Health Fam Med. 2013 Jun;10(2):63-4.

13 Fink et al: Proposed new classification: https://dxrevisionwatch.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/finkproposednewclass1.png

Caveats: The ICD-11 Beta drafting platform is not a static document: it is a work in progress, subject to daily edits and revisions, to field test evaluation and to approval by ICD Revision Steering Group and WHO classification experts. Not all new proposals may survive ICD-11 field testing. Chapter numbering, codes and Sorting codes currently assigned to ICD categories may change as chapters and parent/child hierarchies are reorganized. The public version of the Beta draft is incomplete; not all “Content Model” parameters display or are populated; the draft may contain errors and category omissions.