Submissions to the first DSM-5 stakeholder review (February to 20 April 2010)

Post #85 Shortlink: http://wp.me/pKrrB-19o

Copies of international patient organization submissions to the first DSM-5 stakeholder review were collated on this page of my site, together with selected patient and advocate submissions:

DSM-5 Submissions to the 2010 review: http://wp.me/PKrrB-AQ

Massachusetts CFIDS/ME & FM Association has a page in its Advocacy section dedicated to the organization’s ongoing concerns about the proposals of the DSM-5 Somatic Symptom Disorders Work Group.

Last year, Massachusetts CFIDS/ME & FM Association submitted a response which can be read on their Advocacy pages here or on Dx Revision Watch site here. The first letter was submitted by Dr. Alan Gurwitt, MASS CFIDS/ME & FM Association’s President.

A second letter was submitted by Ken Casanova, a Board member and past President, which wasn’t included with last year’s submissions, on this site. A copy is published below with kind permission of the author:

(From 2010)

Massachusetts CFIDS/ME & FM Association

National advocacy efforts state concerns about revisions to DSM-V

The Massachusetts CFIDS/ME & FM Association has joined with other U.S. patient organizations to advocate against the potential misuse of a proposed new psychiatric diagnostic category in the diagnosis of CFIDS/ME and Fibromyalgia.

The revision of the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV ) is at the core of our concerns. This Manual, published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), contains the major listings, definitions, and explanations of different psychiatric and psychological disorders. It is important to note these classifications are used by insurance companies, Medicaid and Medicare for patient billing purposes.

Currently DSM-IV is undergoing a major revision – the new DSM-V Manual is scheduled to be published in 2013. The issue which has raised the serious concern of both U.S. patient associations and of the international CFIDS/ME researchers (the International Association of CFS/ME – IACFS-ME) is a proposed new psychiatric category titled the:

Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder (CSSD)

to be included in the new DSM-V. More specifically, the way CSSD is defined makes it possible to either mistakenly or intentionally diagnose CFIDS/ME or Fibromyalgia in this psychiatric category. Moreover, the greater concern is whether this change could potentially lead to the reclassification of these illnesses as psychiatric conditions under CSSD.

The crux of the issue is that a person can be psychiatrically diagnosed as having complex somatic symptom disorder if he or she has all of the following:

a) multiple somatic (physical) symptoms, or one severe symptom that have been chronic fatigue for at least six months, and

b) which create a high level of health anxiety and which establish a central role in the patient’s life for health concerns.

Does this diagnosis sound like it could easily be misused to diagnose CFIDS/ME, fibromyalgia, or even many other chronic physical illnesses? U.S. patients have already experienced the problematic history of The Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), The National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the many physicians and researchers discounting CFIDS/ME as a psychiatric illness, maladaptive behavior, or inability to cope with stress. If this new diagnostic code were to be accepted, then patients potentially could be labeled with complex somatic symptom disorder just because they are pushing doctors for answers to many symptoms.

In their explanation of the CSSD diagnosis, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Committee states: “Some patients, for instance, with irritable bowel syndrome or fibromyalgia would not necessarily qualify for a somatic symptom disorder diagnosis.”

As a result, this development galvanized patient associations around the country, as well as the IACFS/ME, to protest any misuse of the new CSSD category. This was accomplished by submitting strong letters on behalf of the illnesses to the APA during the comment period, which closed on April 20, 2010.

On behalf of the Massachusetts CFIDS/ME & FM Association and the community it serves, several poignant letters were written to the APA. The first letter was submitted by Dr. Alan Gurwitt, MASS CFIDS/ME & FM Association’s President. It focused particularly on the incontrovertible medical research clearly demonstrating the biological and physiological bases of the illnesses. A second letter was submitted by Ken Casanova, a Board member and past President. It reviewed in detail how the new CSSD diagnosis would make it more difficult to separate physical from psychiatric illnesses, and how the new diagnosis could be mistakenly or intentionally misused.

The International Classification of Diseases-Clinical Modification 9 (ICD-CM-9) used by the CDC is different than the version used by WHO. The CDC is planning to update the ICD-CM- 9 to the ICD-CM-10 in 2013. However, the International WHO Code is being updated to version ICD-11 in 2014. This means the code the CDC will be using is still behind the WHO. The CFIDS and FM communities’ concern is that the new CSSD classification could influence how CFIDS/ME and FM are listed in both the CDC and WHO classifications.

20+ years after first naming the illness Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, the CDC is now wanting to update its classification. The serious concern is that the new CSDD diagnosis could negatively influence any new CDC listing of CFIDS/ME. Any new psychiatric bias toward CFIDS/ME and/or FM in the new code could make it more difficult for patients to obtain insurance payments for their treatments. There is also, of course, concern about the effect of CSSD on the WHO code.

There is strength in numbers and our organization advocates on behalf of patients and the impact these illnesses have on their lives. Consider joining our Association so that together our voice and our actions will be stronger.

Click here to read Dr. Alan Gurwitt’s letter to APA

Click here to read Kenneth Casanova’s letter to APA

Published with permission of the author

Kenneth Casanova’s letter to DSM-V Committee of the APA

Specifically flawed CSSD diagnosis

Special problems with physiologically-induced pain disorders

CSSD definition is open to misinterpretation

Changes incorporated in CSSD from DSM-IV

CSSD & ICD-10-CM and ICD-11

All Pages

Page 1 of 6

The introductory explanation text of CSSD in the Draft unfortunately lacks the requisite scientific rigor and specificity for medical and psychiatric differential diagnosis.

The CSSD diagnostic criteria in many instances would reasonably diagnose a percentage of patients: such patients would be abnormally concerned/preoccupied with actual medical symptoms, over-interpretation of bodily sensations, or the somatic projection of ideational content – to the point where such processes become pathological. The example of the true hypochondriac or the patient who easily somatizes feelings would validate a portion of the CSSD definition.

However, at the same time, the CSSD criteria is so broad that it draws no clear boundary between the patient responding within normal expectations to an actual medical condition, and patients who are pathologically misapprehending or excessively concerned. By unscientifically conflating two major groups of patients, the draft criteria must result in a substantial number of cases in which reasonable and appropriate patient responses to actual physical illness are falsely psychologized. Such a lack of diagnostic clarity creates an amorphous and contradictory criteria for misdiagnosis – with severe consequences for patient suffering and possible medical malpractice.

Page 2 of 6

Specifically flawed CSSD diagnosis:

The essence of CSSD is to have one severe physical symptom or multiple physical symptoms that are chronic (at least 6 months) and about which an individual either has misapprehended as to its causation or is excessively concerned about or preoccupied with (beyond a realistic viewpoint).

Following the critique above as to the difficulty with the criteria: A person may be fully diagnosed with only the following elements of the definition: (A.) Multiple somatic symptoms or one severe symptom that have been (B.) chronic and persistent for at least six months, and (C.) create a high level of health anxiety and establish a central role in the patient’s life for health concerns.

Can anyone doubt that such a minimal definition could theoretically diagnose anything from true hypochondriasis to severe rheumatoid arthritis, medication resistance epilepsy, to the pain of severe radiculopathy, to drug resistant pelvic inflammatory disease, to a brain tumor, to Lou Gehrig’s disease, to neurofibromatosis, and to many other chronic illnesses. Can such an unscientific and medically questionable diagnostic criteria be contemplated?

Another example may be the early stages of MS: In its early stages MS is difficult to diagnose – in fact decades ago, many physicians believed MS was a psychiatric syndrome.

Page 3 of 6

Special problems with physiologically-induced pain disorders:

A very serious red flag is raised in the actual criteria: ” XXX.3 Pain disorder. This classification is reserved for individuals presenting predominantly with pain complaints who also have many of the features described under criterion B.” Criterion B requires that two of five conditions be met. B’s conditions would be fulfilled if the patient experienced a “high level of health-related anxiety” and that “health concerns assume a central role in their lives”. Medicine currently has come to realize that pain itself can no longer be relegated to the periphery of clinical concern and should no longer be waved off as a “mere symptom” – but should be fully investigated.

Pain is a legitimate medical symptom and is now recognized at the “fifth vital sign” to be evaluated by physicians, along with blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate and temperature. Untreated pain can become very detrimental to a person’s health as well as very disabling. Pain, in the joints, sore throat (chronic mononucleosis, a known medical diagnosis), and other conditions are all too often psychiatrically dismissed. The misleading nature of the diagnosis of pain in the draft CSSD definition can have serious consequences.

Clearly the CSSD disorder is not only theoretically flawed and disparate, but as a practical methodology, it is a potential minefield for medical and psychiatric practices and the patients seeking their assistance.

Page 4 of 6

Language in the Introduction and subsections of CSSD definition is open to misinterpretation:

The Draft explanation of Somatic Symptom Disorders both in its Introduction and subsections clearly demonstrates the lack of precision and the resulting conflation of two disparate medical phenomenon. In the explanation of Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder some selection of text will show the difficulty:

“The hallmark of this disorder is disproportionate or maladaptive response to somatic symptoms or concerns.” Obviously, the word “disproportionate” is a matter of degree or “portion”. The determination of degree cannot be entirely objective, and in cases of actual medical conditions, normal patient response varies across a wide range of factors, including personal, economic, occupational, family, etc. circumstances.

“Patients typically experience distress and a high level of functional impairment.” Such a statement is perfectly consistent with a number of medically understood illnesses, and therefore in the problematic context of the CSSD criteria can be disorienting and misleading. “Sometimes the symptoms accompany diagnosed general medical disorders…”

“There may be a high level of health care utilization…” No experienced specialist or general physician is unaware of cases in which patients have had to see five or more doctors before receiving an accurate diagnosis – especially with the more difficult to diagnose illnesses. Endocrine, hematological, circulatory, occult pulmonary conditions come to mind.

“In severe cases, they may adopt a sick role.” Now the concept of the “sick role” may infrequently constitute a distinctly categorical “role-type” that is pathological and somewhat separable from a real physiological illness. However, in many chronic illnesses, whose symptoms wax and wane in severity – it would be more accurate to say that the person is chronically sick. Undoubtedly, different individuals or even the same individual will adapt or respond variously, with an attitude of courage, hopefulness, worry, or even despair in different times or circumstances. However, to label such common variations as a “sick role” can often be too superficial and facile – a false engagement in type-casting. To be sure, many patients who are chronically ill need intelligent counseling in coping and in modulation of their attitude and emotions. Hopelessness can creep in and assistance is needed – but to label as a psychiatric disorder a normal spectra of physical disorder with emotional and mental sequelae is a distortion. Again, in some cases the viewpoint is accurate, but in too many others a distortion with consequences.

“Some patients feel that their medical assessment and treatment have been inadequate.” In some cases, this statement reflects an adequate further description of a psychiatric problem. In other cases, the statement demonstrates a failing in the criteria.

Again, the dual nature of the criteria is reflected in the following wording: “Patients with this diagnosis typically have multiple, current, somatic symptoms that are distressing…The symptoms may or may not be associated with a known medical condition. Symptoms may be specific…or relatively non-specific (e.g., fatigue or multiple symptoms.)” Note: The classification or facile diversion of fatigue to the psychological realm can be a very medically dangerous undertaking. A multitude of serious medical, and currently poorly understood biological conditions, manifest fatigue as an early and chronic symptom.

“… Such patients often manifest a poorer health-related quality of life than patients with other medical disorders and comparable symptoms.”

Unfortunately this statement represents perhaps the nadir of scientific thinking in the entire statement, and therefore puts in relief the lack of rigor which proceeds and follows it. Yes, patients with one medical disorder will often have a poorer quality of life than those with another medical disorder.

In the Introduction to this section in the Draft, there is some clarity in attempting to set a line between the pathological and normal response to medical illness:

“Having somatic symptoms of unclear etiology is not in itself sufficient to make this diagnosis. Some patients, for instance with irritable bowel syndrome or fibromyalgia would not necessarily qualify for a somatic symptom disorder diagnosis.” But looking underneath the text raises questions: is the diagnosis of fibromyalgia itself uncertain; or alternatively, is the question the addition of CSSD to some cases of fibromyalgia? By what criteria would CSSD be added: what is a within the range of normal varying responses to a chronic illness, and which responses would add a psychiatric diagnosis? The criteria leave these questions open.

Page 5 of 6

Changes incorporated in CSSD from DSM-IV

Another major aspect of the new CSSD criteria is its departure from the various qualifying distinctions contained within the several previous diagnostic categories it replaces.

These previous diagnoses, to be obliterated and incorporated within the more diffuse CSSD, are: Somatization disorder; Undifferentiated Somatoform disorder; Hypochondriasis; Pain Disorder Associated with Both Psychological Factors and a General Medical Condition; and Pain Disorder Associated with Psychological Factors.

A major question is: what is lost, if anything, in the “lumping” of the older conditions? Moreover, what, if anything, that is lost provided more rigorous procedures for making more accurate diagnoses – or at least less inaccurate?

Somatization disorder requires a history of many physical complaints before the age of 30. The new CSSD throws this qualification overboard. Why the change? Has the historical finding, which has counted as a distinct marker, evaporated?

A second major change is that fatigue, a symptom highlighted in the statement about CSSD, is specifically stated as not a symptom found in somatization disorder. This issue of fatigue directly impacts the differential diagnosis between the proposed CSSD definition and the physiological, multi-systemic illness of CFS – also known in Europe as myalgic encephalopathy or myalgic encephalomyelitis. Somatization disorder would be hard to confuse with CFS, for instance sleep disorder and decreased concentration are not physical symptoms included in the diagnosis of somatization disorder. Also in somatization disorder, head, joint and possible muscle pain are the only stated symptoms in common with those of CFS/ME. Yet the CSSD criteria, with a psychological not a medical interpretation will provide a diagnosis of CFS/ME.

Eliminating distinctions of somatization disorder negates distinctions that must have taken years to discriminate.

A second diagnostic criteria transformed/lumped into CSSD is Undifferentiated Somatoform Disorder. This diagnosis instead of simply relying upon multiple somatic symptoms (CSSD) actually group specific symptoms necessary for diagnostic fulfillment.

These include: “One or more physical complaints (e.g., fatigue, loss of appetite, gastrointestinal or urinary complaints) which either 1) the symptoms cannot be fully explained by a known general medical condition, or 2) when there is a medical condition are excessive in relation to the condition.” In this condition, as in CSSD, much of the differential diagnosis depends on the interpretation of the individual physician – whether medical or psychological or both.

Yet the new CSSD definition simply widens further the amount of undifferentiated territory. Is negation of diagnostic detail supportable, and again what are the practical consequences.

Issues related to possible coordination of DSM-V with CDC publication of ICD-10-CM and WHO ICD-11:

There is discussion that: “The APA [the American Psychological Assn., the sponsor of the new DSM-V] has already worked with the CMS [U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services] and CDC to develop a common structure for the currently in-use DSM-IV and the mental disorders section of the ICD-10-CM.”

The ICD-10-CM, overseen by the C.D.C, will be a revised coding system in the U.S. for all diseases and conditions. This coding system includes disorder names, logical groupings of disorders and code numbers. The new ICD-10-CM will contain codes for all Medicare and Medicaid claims reporting. The ICD-10-CM is scheduled to be published Oct. 1, 2013.

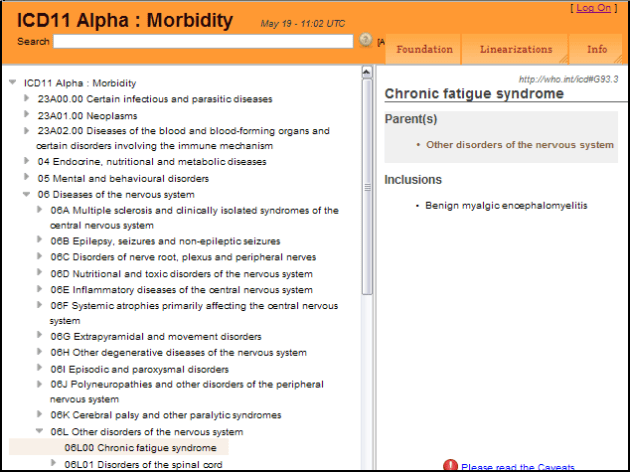

Currently the coding system in the U.S. is the ICD-9-CM. The U.S. Coding System is separate from the international coding system under the auspices of the World Health Organization. The WHO system is currently the ICD-10. WHO will be revising its system in 2014 to the ICD-11.

Page 6 of 6

Concerns about confusion of CSSD with CFS/ME and fibromyalgia in DSM-V, ICD-10-CM and ICD-11.

CFS/ME and fibromyalgia medical researchers, patients and patient organizations are rightly concerned that flawed CSSD definition will adversely affect CFS/ME and fibromyalgia research and clinical care through the application of DSM-V; as well as any coordination of the CSSD diagnosis with the coding of CFS/ME and FM in the ICD-10-CM and ICD 11.

The real issues for CFIDS-ME and FM are two.

If the CSSM diagnosis appears in either of the new ICD codings, there are two possibilities. First, by itself, the new CSSM diagnosis would be more confused with CFIDS/ME and FM than any of the DSM-IV diagnostic categories.

Second, what would be the influence of the diagnostic category of CSSD in the direct categorization of CFIDS/ME and FM in both the new WHO definitions and the U.S. definitions. The categorization of CFIDS/ME and FM could be directly applied to the CSSD definition; or alternately be redefined, detrimentally, in other WHO ICD or CDC ICD categories. Certainly, cooperation of the APA, WHO and CDC is expected and very useful – except when a flawed category is shared.

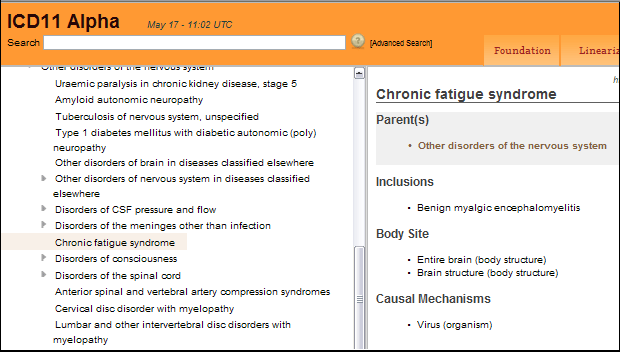

Moreover, the direct categorization of CFIDS/ME historically both in the WHO ICD-10 and the CDC ICD-9-CM (both current) must be noted. WHO has been clearly the more medically progressive and accurate. The ICD-10 since 1990 has listed CFS/ME under G93.3 “neurological disorders”. During the same period of time through to the present, the CDC has instead listed CFS under R53.82 under the general category of Symptoms, Signs and Ill-Defined Conditions as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (780.71). Many efforts have been made to get the CDC to reassign CFIDS/ME to the neurological section, but the CDC has resisted. Under the U.S. system CFIDS/ME has been listed as a vague syndrome as opposed to a defined disease entity, thereby undermining its medical credibility.

How will the APA’s new definition of CSSD – which could misdiagnose CFIDS/ME -influence the CDC’s publication of the new U.S. ICD-10-CM?

CFS/ME and FM patients and organizations sincerely hope that the APA will be mindful of the detrimental effects that the flawed CSSD category could have on the ICD codings.

All new ICD-10-CM coding categories will be mandatory for reimbursement for Medicare and Medicaid and are also widely used by private insurance companies. A flawed classification of CFS-ME and FM in any of the new systems – DSM-V, ICD-10-CM or ICD-11 will have both medical system access consequences, as well as diagnostic ramifications, that could place greater focus on CFS-ME and FM as psychiatric disorders as opposed to a medical/biological disorders.

Conclusion

CFS/ME and FM through intense medical research over the past 20 years have been demonstrated to be complex, multi-systemic, biological illnesses. The illnesses follow from initial infectious or toxic triggers and involve dysregulation of the multiple body systems, including the immune, nervous, endorcrine, cardio-vascular systems. Certain viruses have long been implicated. Genetic and genomic factors are being elucidated.

Dr. Anthony Komaroff, Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and long-time researcher in the field has said the following: “there are now 4,000 published studies that show underlying abnormalities in patients with this illness [CFS/ME]. It is not an illness that people simply can imagine that they have and it’s not a psychological illness. In my view, that debate, which has been wage for more than twenty years, should now be over.”

The diagnosis of CSSD is flawed in and of itself, in its application to a variety of medical illnesses and specifically to CFS/ME and FM.

Sincerely,

Kenneth Casanova