ICD-11 Content Model Reference Guide: version for December 2010

February 18, 2011

ICD-11 Content Model Reference Guide: version for December 2010

Post #62 Shortlink: http://wp.me/pKrrB-Xj

Update @ 1 March 2011

A more recent version of the Content Model document was uploaded to the ICD Revision site on 22 February.

It can be accessed here on the ICD Revision site:

Or opened here on DSM-5 and ICD-11 Watch site: Content Model Reference Guide v January 2011

A revised version of the ICD-11 Content Model Reference Guide was uploaded to the WHO’s ICD Revision Google site in January. This version of the document, dated 27 January 2011, replaces previous versions on DSM-5 and ICD-11 Watch site and on the ICD Revision Google site.

Content Model Reference Guide December 2010 v.1 27 Jan 2011

A copy of this 57 page document can be viewed on the ICD Revision Google site from this page:

http://sites.google.com/site/icd11revision/home/documents

or open here on DSM-5 and ICD-11 Watch site: Content Model Reference Guide December 2010 [v.1]

Introductory pages

ICD-11 alpha

World Health Organization, Geneva

Content Model Reference Guide 11th Revision

December 2010

Table of Contents

Page 2

Introduction 3

What is the “Content Model”? 4

Explanations on the Content Model 5

Technical Specifications for the Content Model 7

ICD -11 Alpha Content Model 9

1. ICD Entity Title 9

2. Classification Properties 11

3. Textual Definition(s) 17

4. Terms 21

5. Body Structure Description 24

6. Temporal Properties 27

7. Severity Properties 31

8. Manifestation Properties 33

9. Causal Properties 35

10. Functioning Properties 38

11. Specific Condition Properties 42

12. Treatment Properties 44

13. Diagnostic Criteria 45

Section B 46

Appendices 48

Appendix 1: Body Systems Value Set 48

Appendix 2: Temporal Properties Value Set 49

Appendix 3: Temporal Properties Value Set and explanations 50

Appendix 4: Basic Aetiology Value Set 56

Appendix 5: Grammar Rules for Titles and Synonyms 57

Page 3

Reference Guide on the Content Model of the ICD 11α

Introduction

This Reference Guide is intended to define and explain the Content Model used in the ICD-11 alpha draft in practical terms. It aims to guide users to understand the purposes and parameters of the Content Model.

The Reference Guide also informs users about the technical specifications of each parameter which the designers of the iCAT (the computer platform that is used to fill in the content model: international Collaborative Authoring Tool) took into account in building the software.

Accordingly, information on each parameter is given in two sections:

(1) Explanations

(2) Technical specifications

The purpose of this Reference Guide is to ensure that the Content Model and its different parameters are properly understood.

This document will be periodically updated in response to user needs and evolution of the content model.

Brief introduction to the ICD – International Classification of Diseases

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is the global standard to report and categorize diseases in order to compile health information related to deaths, illness and injury. The ICD content includes diseases and a range of health problems including disorders, syndromes, signs, symptoms, abnormal findings, complaints, social circumstances, and external causes of injury. The ICD is designed to promote international comparability in the collection, processing, classification, and presentation of these statistics.

In ICD there are multiple classification categories which are defined by explicit or implicit parameters such as: codes, titles, definitions and other characteristics. In ICD 11, we aim to formally represent all this classification knowledge in a systematic way. The Content Model serves this purpose.

Page 4

What is the “Content Model”?

The Content Model is a structured framework that defines “a classification unit” in ICD in a standard way in terms of its components that allows computerization.

A “model” is a technical term that refers to a systematic representation of knowledge that underpins any system or structure. Hence, the content model is an organized description of an ICD unit with its different parameters.

In the past, ICD did not explicitly define its “classification units” – in other words diseases were classified without defining “what is a disease?” (There have been efforts to provide some definitions, inclusions, exclusion information, and some coding rules in the instructions and in the index. Some chapters, such as mental health, oncology, or other groups of diseases have been elaborated with diagnostic criteria. All these efforts may be seen as implicit modelling.) In the ICD 11 revision process, deliberate action is being taken to define the ICD categories in a systematic way and represent the classification knowledge to allow processing within computer systems.

To achieve this aim, different ICD categories have been defined by user groups as to what they are. For example, first a disease was defined as follows:

A disease is a set of dysfunction(s) in any of the body systems defined by:

1. Symptomatology: manifestations: known pattern of signs, symptoms and related findings

2. Aetiology: an underlying explanatory mechanism

3. Course and outcome: a distinct pattern of development over time

4. Treatment response: a known pattern of response to interventions

5. Linkage to genetic factors: e.g., genotypes, patterns of gene expression

6. Linkage to interacting environmental factors

Then the key components of this definition have been operationally defined as different parameters which, as a whole, formed the Content Model.

Page 5

Explanations on the Content Model:

A classification unit in ICD is called an “ICD entity”. In other words, any distinct classification rubric is called an Entity. (The term “Entity” is used interchangeably – in the same meaning — with the term “ICD Concept”.

An ICD entity may be:

– A category

– A block

– A chapter

A category (which is the most common reference to an ICD class) may be a disease, disorder or syndrome; sign, symptom or other health problem such as injuries, or a combination of the above. In addition, ICD has also been used to classify “external causes” or “other reasons for encounter” which are different kinds of entities than the diseases. In other words, “Category” refers to the individual classes represented in the ICD-10 printed version.

The Content Model, therefore, allows the various classification categories to be represented more clearly so that users can identify the classification units in a scientific fashion.

The purpose of the content model is to present the knowledge that lies under the definition of an ICD entity. Each ICD entity can be seen from different dimensions. The content model represents each one of these dimensions as a “parameter”. For example, there are currently 13 defined main parameters in the content model to describe a category in ICD.

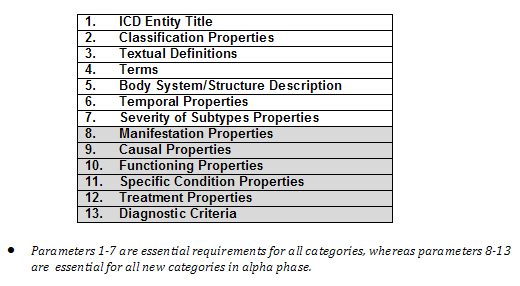

TABLE 1: The Content Model main parameters

For each category, various parameters are given different values. For example:

Category: Myocardial Infarction

Parameters: Value:

Body system Cardiovascular system

Body part Heart

Signs/symptoms Crushing chest pain, etc.

Investigation Findings ST elevation in ECG

It is not necessary to describe all categories with all parameters. Only parameters that are relevant to the description of the category should be used. In certain instances such as External Causes, only a number of the parameters are valid for the description of these entities.

The full range of different values for a given parameter is predefined using standard terminologies and ontologies. The predefined values constitute a “value set”.

Read full document here: Content Model Reference Guide December 2010 [v.1]

Related documents:

Paper:

http://bmir.stanford.edu/file_asset/index.php/1522/BMIR-2010-1405.pdf

A Content Model for the ICD-11 Revision

Samson W. Tu1, Olivier Bodenreider2, Can Çelik3, Christopher G. Chute4, Sam Heard5, Robert Jakob3, Guoquian Jiang4, Sukil Kim6, Eric Miller7, Mark M. Musen1, Jun Nakaya8, Jon Patrick9, Alan Rector10, Guillermo Reynoso11, Jean Marie Rodrigues12, Harold Solbrig4, Kent A Spackman13, Tania Tudorache1, Stefanie Weber14, Tevfik Bedirhan Üstün3

1Stanford Univ., Stanford, CA, USA; 2National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA; 3World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; 4Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, MN, USA; 5Ocean Informatics, Chatswood, NSW, Australia; 6Catholic Univ. of Korea, Korea; 7Zepheira, Fredricksburg, VA, USA; 8Tokyo Medical and Dental Univ., Tokyo, Japan; 9Univ. of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia; 10Univ. of Manchester, Manchester, UK; 11Buenos Aires, Argentina;12Université de Saint Etienne, Saint Priest en Jarez, France; 13IHTSDO, USA; 14DIMDI – German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information, Köln, Germany

Abstract

The 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) will be developed as a collaborative effort supported by Webbased software. A key to this effort is the content model designed to support detailed description of the clinical characteristics of each category, clear relationships to other terminologies and classifications, especially SNOMED-CT, multi-lingual development, and sufficient content so that the adaptations for alternative uses cases for the ICD – particularly the standard backwards compatible hierarchical form – can be generated automatically. The content model forms the basis of an information infrastructure and of a webbased authoring tool for clinical and classification experts to create and curate the content of the new revision.