September 6, 2010

by meagenda

Update on the ICD-11 Alpha Draft at 06.09.10

Post #47 Shortlink: http://wp.me/pKrrB-MD

The information in this update relates only to proposals for ICD-11.

This information does not apply to ICD-10-CM, the forthcoming “Clinical Modification” of ICD-10, which is scheduled for implementation in October 2013 and is specific to the US.

Post #45 is intended to clarify any confusion between ICD-10, ICD-11 and the forthcoming US specific “Clinical Modification”, ICD-10-CM.

See: US “Clinical Modification” ICD-10-CM

On 7 June, in Post #46, I published a report that includes 13 screenshots from the iCAT, the wiki-like Web 2.0 collaborative authoring platform through which ICD-11 is being drafted.

To view proposals as they currently appear in the iCAT, see the screenshots and my brief notes here:

PVFS, ME, CFS: the ICD-11 Alpha Draft and iCAT Collaborative Authoring Platform

Note that what currently appears in the iCAT and in my June report may be subject to revision by the ICD Revision Steering Group and Topic Advisory Groups prior to an alpha draft being publicly released or presented at the forthcoming September iCamp2 meeting.

Update on the ICD-11 Alpha Draft

ICD Revision maintains a website at: http://sites.google.com/site/icd11revision/

where the public can access minutes of iCamp and Topic Advisory Group (TAG) meetings, meeting agendas, key documents and presentations.

Text on this website had read:

“ICD-11 alpha draft will be ready by 10 May 2010

ICD-11 beta draft will be ready by 10 May 2011

ICD final draft will be submitted to WHA by 2014”

This text has recently been changed to read:

“ICD-11 alpha draft process began September 2009

ICD-11 beta draft process will begin in 2011

ICD final draft will be submitted to WHA by 2014”

No detailed timeline has been published but there is a “Project milestones and budget, and organizational overview” on page 7 of this document:

ICD-11 Revision Project Plan – Draft 2.0 (v March 10) PDF: ICD Revision Project Plan

or: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICDRevisionProjectPlan_March2010.pdf

which projects a Beta Draft release for May 2012.

Release of ICD-11 Alpha Draft

No ICD-11 Alpha Draft was publicly released in May. But a hard copy “snapshot” of the alpha, as it stood at that point, was presented by the WHO at the 63rd World Health Assembly meeting, between 17 and 25 May.

September iCamp2 meeting

An ICD Revision iCamp2 meeting had been scheduled for April but was postponed. The meeting has been rescheduled for later this month.

iCamp2 is now scheduled for 27 September – 1 October 2010, in Geneva.

The revised Agenda for this meeting is here:

http://sites.google.com/site/icd11revision/home/face-to-face-meetings/icamp2-2010

http://sites.google.com/site/icd11revision/home/face-to-face-meetings/icamp2-2010/icamp-2-agenda

Following iCamp meetings, PowerPoint presentations are sometimes made publicly available on the website.

According to sources, the print version of the alpha draft is now expected to be made available around the time that the iCamp2 meeting takes place, later this month.

ICD Revision maintains a blog, here, which hasn’t been updated since last October and a Facebook presence here

In response to some questions raised several months ago, ICD Revision confirmed, on 6 August, that:

“A draft print version will be available in September 2010.”

On 7 August, I raised the following:

“ICD Revision has clarified that a draft print version will be available in September 2010.

Clarification would also be welcomed on whether this Alpha Draft will be available for internal use only or intended for public viewing, and if for public viewing, in what format(s)?

According to the Revision document ICD Revision Project Plan [1], published on the ICD Revision Google site, in March:

‘The Alpha draft will be produced in a traditional print and electronic format. The Alpha Draft will also include a Volume 2 containing the traditional sections and including a section about the new features of ICD-11 in line with the style guide [2]. An index for print will be available in format of sample pages. A fully searchable electronic index using some of the ontological features will demonstrate the power of the new ICD.’

Since 2007, it has been possible for stakeholders in the development of ICD-11 to submit proposals and comments, supported by citations, via the ICD Update and Revision Platform Intranet. It was understood last year, that for some Topic Advisory Groups a proposal form for ICD-11 was being prepared for use by stakeholders. Information about the availability of proposal forms for the various Topic Advisory Groups, up to what stage in the development process timeline these might be used, and which stakeholders would be permitted to make use of proposal forms would be welcomed.

It remains unclear what will be ready by September, whether it will be available for public scrutiny, and in what format(s), and by what various means stakeholders might submit proposals prior to and following the release of an Alpha Draft.”

This request for clarification has yet to receive a response.

Current proposals for the classification and coding of PVFS, ME and CFS for the ICD-11 Alpha Draft

On my DSM-5 and ICD-11 Watch website, at Post #46, is a report I published on 7 June that includes screenshots from the iCAT, the wiki-like collaborative authoring platform through which ICD-11 is being drafted.

To view what is currently visible in the iCAT, see the screenshots and my brief notes here:

PVFS, ME, CFS: the ICD-11 Alpha Draft and iCAT Collaborative Authoring Platform, 7 June 2010

Caveat

For better understanding, it is important that the brief iCAT Glossary page is read in conjunction with the iCAT screenshots, especially the Glossary entries for ICD-10 Code; ICD Title; Definition; Terms: Synonyms, Inclusions and Exclusions [4].

Read the iCAT Glossary here: http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icatfiles/iCAT_Glossary.html

Secondly, it needs to be understood that the alpha draft is a “work in progress”. Not all content will have been compiled yet and entered into the iCAT and there are many blank fields awaiting population for all chapters and for all categories. It also needs to be understood that some text already entered into the various “Details” fields may still be in the process of internal review and subject to revision.

Because Topic Advisory Groups are still in the process of entering content into the iCAT not all listings and content that is intended to be included in the print version of the alpha draft may be visible to us, at this point, in the iCAT drafting platform.

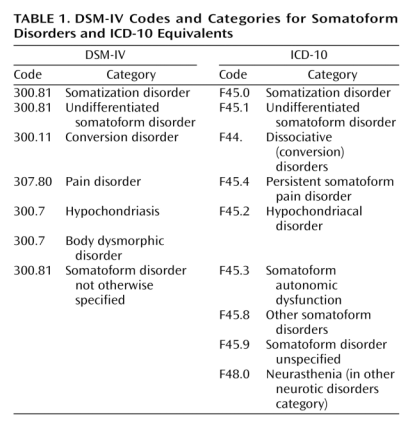

ICD-10 > ICD-11

One of the biggest changes between ICD-10 and ICD-11 is that in ICD-11, Categories will be defined through the use of multiple parameters.

In ICD-10, there is no textual content for the three terms “Postviral fatigue syndrome”, “Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis” and “Chronic fatigue syndrome”. There are no definitions and the relationship between the three terms is not specified.

But in ICD-11, categories will be defined through the use of multiple parameters: Title & Definition, Terms: Synonyms, Inclusions, Exclusions, Clinical Description, Signs and Symptoms, Diagnostic Criteria and so on, according to a common “Content Model” [2] and as evidenced by the screenshots.

So have a look at Post #46 if you have not already done so. Or have a poke around in the iCAT wiki production server. The public has no editing rights so you can’t break anything [3].

Request for clarification to Advisory Group for Neurology

On 28 June, I contacted Dr Raad Shakir who chairs the ICD Revision Topic Advisory Group for Neurology, for clarifications in respect of current proposals for ICD-11 Chapter 6 (VI).

Dr Shakir has been asked if he would disambiguate current proposals for ICD-11 for the classification of, and relationships between the three terms, “Postviral fatigue syndrome”, “Chronic fatigue syndrome” and “Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis”, since this is not explicit from the information as it currently displays in the iCAT, nor from the Discussion Note for “Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome”, which has been listed in Chapter 6 (VI) under

Chapter 6 (VI) Disorders of the nervous system

> GN Other disorders of the nervous system

(“Gj92” is a “Sorting label”. It is understood that a “Sorting label” is a string that can be used to sort the children of a category and is not the ICD code.)

I was advised by Dr Shakir, on 5 July, by email, that my queries have been passed to the Advisory Group for a response. I have yet to receive a clarification.

To: Dr Raad Shakir, West London Neurosciences Centre, Charing Cross

Hospital, Fulham Palace Road, London W6 8RF raad.shakir@imperial.nhs.uk

Re: Query in relation to Topic Advisory Group for Neurology proposals for ICD-11 Chapter 6 (VI)

28 June 2010

Dear Dr Shakir,

I am writing to you in your capacity as Chair, ICD Revision TAG Neurology, with a request for clarification of current proposals for the restructuring of categories classified in ICD-10 under G93 Others disorders of brain, specifically those at G93.3. That is:

Diseases of the nervous system (G00-G99)

> Other disorders of the nervous system (G90-99)

> G93 Other disorders of brain

[…]

G93.3 Postviral fatigue syndrome

Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis

(with Chronic fatigue syndrome indexed to G93.3 in ICD-10: Volume 3: The Alphabetical Index)

In the absence of the release of an ICD-11 Alpha Draft, I rely on information as it currently displays in the ICD Categories listed in the iCAT production server at: http://icat.stanford.edu/

My understanding is that what is being proposed at this point for ICD-11 is that ICD categories coded between G83.9 thru G99.8 in ICD-10 Chapter VI: Diseases of the nervous system, are being reorganised.

That in ICD-11, Chapter 6 (VI) codings beyond G83.9 are represented by new parent classes numbered GA thru to GN thus:

Chapter 6 (VI) Disorders of the nervous system

[…]

G80-G83 Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes

GA Infections of the nervous system

GB Movement disorders and degenerative disorders

GC Dementias

[…]

GN Other disorders of the nervous system

That “GN Other disorders of the nervous system” is parent to five child classes that are assigned the “Sorting labels” Gj90-Gj94.

(It is understood that a “Sorting label” is a string that can be used to sort the children of a category and is not the ICD code.)

At Gj92, sits “Chronic fatigue syndrome”

That “Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome” displays no child classes of its own.

The Category Note associated with “Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome” records a Change in hierarchy for class: G93.3 Postviral fatigue syndrome because its parent category (G93 Other disorders of brain) is removed.*

[*Ed: Note that the removal of the parent “G93 Other disorders of brain” affects many other categories also classified under G93 in ICD-10, not just G93.3, which have also been assigned “Sorting labels”.]

According to the iCAT ICD Categories “Details for Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome”

“Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome” displays as a ICD Title term.

“Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome” has a Definition field populated.**

[**Ed: Which may be subject to revision and in response to proposals.]

It has an External Definitions field populated which includes definitions imported from other classification systems, the text of which includes “Also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis”.

It has “Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis” specified under Inclusions.

It has no Synonyms, Exclusions or other descriptor fields populated yet.

That at this point and as far as the iCAT version displays, there is no explicit accounting for “Postviral fatigue syndrome”, as an entity, other than that “Postviral fatigue syndrome” is specified under Exclusions to Chapter 5 (V) F48.0 Neurasthenia and to Chapter 18 (XVIII) R53 Malaise and fatigue and is referenced in these chapters as

postviral fatigue syndrome G93.3 -> Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome

It is further understood, from the iCAT Glossary at

http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icatfiles/iCAT_Glossary.html

that:

“Inclusion terms appear in the tabular list of the traditional print version and show users that entities are included in the relevant concept. All of the ICD-10 inclusion terms have been imported and accessible in the iCat. These are either synonyms of the category titles or subclasses which are not represented in the classification hierarchy. Since we have synonyms as a separate entity in our ICD-11 content model, the new synonyms suggested by the users should go into the synonyms section. In the future, iCat will provide a mechanism to identify whether an inclusion is a synonym or a subclass.”

I should be most grateful if you could clarify the following for me:

1] In ICD-10 Volume 3: The Alphabetical Index, “Chronic fatigue syndrome” is indexed to G93.3 but does not appear in the Tabular List.

In ICD-11, is it being proposed that “Chronic fatigue syndrome” will be included in the Tabular List in Chapter 6 (VI) Diseases of the nervous system under “(GN) Other disorders of the nervous system”?

2] In ICD-11, is it being proposed that rather than “Postviral fatigue syndrome” being the ICD Category Title term (previously coded at G93.3, but which has now lost its parent class, G93) that “Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome” is proposed as a new ICD Category Title term?

If this is the case, what is the current proposed relationship between the terms “Postviral fatigue syndrome” and “Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome”?

That is, is it proposed that in the tabular list, “Postviral fatigue syndrome” would still appear as a discrete Category Title term or is it intended that it should be subsumed under “Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome” or become a Subclass of, or Synonym to “Chronic fatigue syndrome”, or to have some other relationship?

3] In the iCAT, the term “Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis” (previously coded at G93.3, but which has now lost its parent class G93) is listed as an Inclusion under “Details for Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome” but does not appear listed under “GN Other disorders of the nervous system” in the ICD Category List with a Sorting label of its own, nor as a child to “Gj92 Chronic fatigue syndrome”.

What is currently being proposed for ICD-11 for the classification and coding of “Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis”, as an entity, and its relationship to “Chronic fatigue syndrome”?

Since this is not explicit from the information as it currently displays in the iCAT, nor from the Discussion Note to Gj92, I should be pleased if you could disambiguate current proposals for the classification of, and relationships between these three terms for ICD-11.

Sincerely,

etc

I will update when a response has been received and when further information about a print version of the alpha draft becomes available.

Other than making general enquiries around the development of ICD-11 and the operation of the iCAT and this request for clarification of current proposals, I have made no representations to any ICD Topic Advisory Group, nor submitted any proposals through any means nor have I had any discussions with WHO personnel or Topic Advisory Group members in relation to current or future proposals for the three terms of interest to us.

References:

PVFS, ME, CFS: the ICD-11 Alpha Draft and iCAT Collaborative Authoring Platform, 7 June 2010, Post # 46: http://wp.me/pKrrB-KK

[1] ICD-11 Revision Project Plan – Draft 2.0 (v March 10):

Describes the ICD revision process as an overall project plan in terms of goals, key streams of work, activities, products, and key participants: ICD Revision Project Plan

http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/ICDRevisionProjectPlan_March2010.pdf

[2] Content Model Specifications and User Guide (v April 10):

Identifies the basic properties needed to define any ICD concept (unit, entity or category) through the use of multiple parameters: http://tinyurl.com/ICD11ContentModelApril10

[3] iCAT production server and Demo and Training iCAT Platform:

http://sites.google.com/site/icd11revision/home/icat

iCAT production server: http://icat.stanford.edu/

[4] iCAT Glossary

http://apps.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icatfiles/iCAT_Glossary.html