Update on the status of the classification of PVFS, ME and CFS for ICD-11: Part Three: WHO rejects Dr Dua’s proposal

November 22, 2018

Post #346 Shortlink: https://wp.me/pKrrB-4wZ

Related posts:

Update on the status of the classification of PVFS, ME and CFS for ICD-11: Part One

Update on the status of the classification of PVFS, ME and CFS for ICD-11: Part Two

Part Three (and it’s good news, for once)

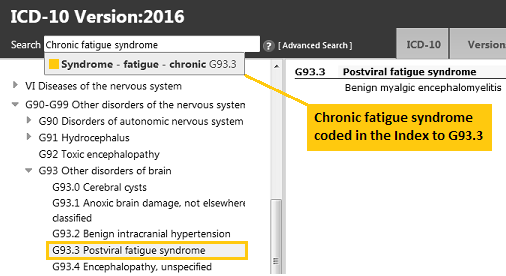

As reported in Parts One and Two, three proposals for the ICD-10 G93.3 legacy categories, Postviral fatigue syndrome; Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis; and Chronic fatigue syndrome have sat unprocessed in the ICD-11 Proposal Mechanism for over a year:

the proposal by Dimmock & Chapman (submitted March 26, 2017);

the proposal by Dr Lily Chu on behalf of the IACFS/ME (submitted March 31, 2017);

the proposal by Dr Tarun Dua (submitted November 06, 2017).

If you are not registered for access to the ICD-11 Proposal platform, click to download the proposal submitted by Dimmock & Chapman in PDF format.

Dr Tarun Dua’s proposal to kick the G93.3 legacy categories out of the Neurology chapter

Dr Tarun Dua is a medical officer working on the Program for Neurological Diseases and Neuroscience, Management of Mental and Brain Disorders, WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. This WHO department has responsibility for both mental disorders and neurological diseases and disorders. Its Director is Dr Shekhar Saxena.

Dr Dua had acted as lead WHO Secretariat and Managing Editor for ICD Revision’s Topic Advisory Group (TAG) for Neurology, which was chaired by Prof Raad Shakir.

When Dr Dua submitted a proposal, last year, recommending that “Myalgic encephalitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)” [sic] should be removed from the Diseases of the nervous system chapter and reclassified in the Symptoms, signs chapter as a child under Symptoms, signs or clinical findings of the musculoskeletal system, it was initially unstated whose position this controversial recommendation represented.

Read Dr Dua’s proposal in PDF format from Page 5 of this November 2017 commentary.

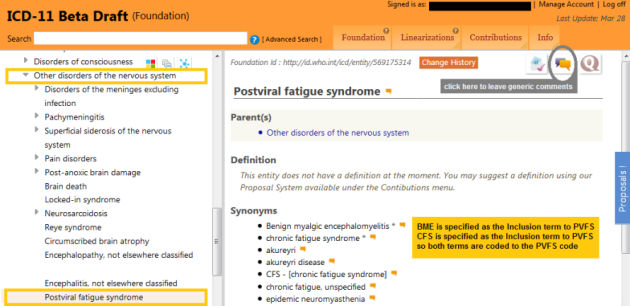

TAG Neurology had ceased operations in October 2016, leaving proposals for the G93.3 legacy categories hanging and the terms still unaccounted for in the public version of the ICD-11 Beta draft. The terms were eventually restored to the draft in March 2017.

Since early 2017, we had been advised several times by senior WHO officers that decisions regarding these categories were “on hold” while an in-house evidence review was being undertaken.

Moreover, WHO senior classification expert, Dr Robert Jakob, had assured me (via email in March 2017) that WHO had no intention of dumping these categories in the Symptoms, signs chapter — yet here was Dr Dua calling for precisely that.

The key question being: Did this recommendation represent the outcome of a now concluded evidence review or did it represented only the position of Dr Dua?

Dr Dua eventually stated that “…the proposal [had] been submitted on behalf of Topic Advisory Group (TAG) on Diseases of the Nervous System, and reiterates the TAG’s earlier conclusions.” But neither Dr Dua nor her line manager, Dr Saxena, were willing to provide us with responses to other queries raised in relation to this proposal, including, crucially: How does this proposal relate to the in-house evidence review?

We were subsequently advised by WHO’s Dr John Grove (Director, Department of Information, Evidence and Research) that the systematic evidence review would determine if the terms needed to be moved to any other specific chapter of ICD-11 and that the outcomes would be provided for review by the Medical Scientific Advisory Committee (MSAC).

A formal response by Dimmock & Chapman to Dr Dua’s proposal can be read in PDF format here Response by Dimmock & Chapman to Dr Tarun Dua proposal of November 6, 2017.

WHO rejects Dr Dua’s proposal

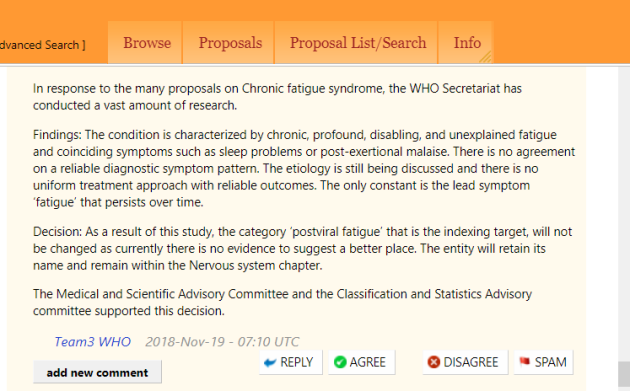

On November 19, the proposal was marked as Rejected by ICD-11 Proposal Mechanism admins:

Screenshot: Accessed November 20, 2018:

https://icd.who.int/dev11/proposals/f/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/569175314

This decision to reject Dr Dua’s recommendation that the terms should be relocated under the Symptoms, signs chapter is accompanied by a brief rationale from ICD-11 Proposal Platform admins “Team3 WHO”:

Screenshot: Accessed November 22, 2018:

Importantly, the decision to retain the terms in the Disorders of the nervous system chapter is supported by the WHO MSAC and CSAC committees.

(See Reference 10 for WHO/ICD-11’s guiding principles for consideration of legacy terms and potential chapter relocations — guidance with which Dr Dua is familiar and has cited, herself, when drafting other proposals, but which she evidently chose to disregard in the case of the G93.3 legacy categories.)

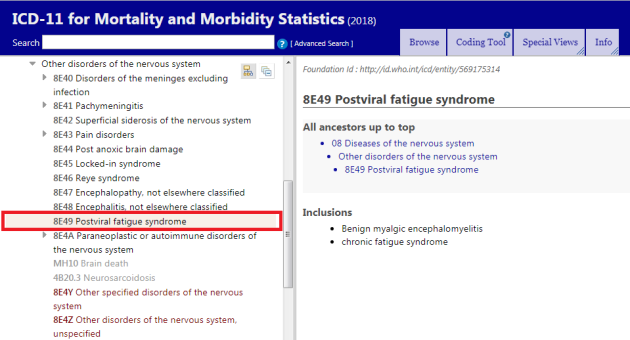

This means that these ICD-10 legacy terms continue to stand as per the “Implementation” version of the ICD-11 MMS that was published in June 2018:

https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f569175314

But we are not done yet…

It’s not known when the remaining proposals submitted by myself and jointly with Mary Dimmock will be processed.

There remains a backlog of over 1000 unprocessed proposals, a number of which had met the March 30, 2017 proposal deadline and were expected to have been processed last year, in time for consideration for inclusion in the June 2018 “Implementation” release.

According to summary reports of the WHO-FIC Network Council’s April 26 and September 26, 2018 teleconferences:

- Between June 2018 and the 2019 [World Health Assembly] resolution, WHO will work to improve user guidance around the classification and any final sorting of the extension codes, but there is not an intention to “reopen the package” of ICD-11 or to make major changes

- The codes will not change after June 2018, and the URIs [Unique Reference Identifiers] will remain the constant, immoveable identifiers for each concept that underpin the classification

- An update cycle was agreed by JTF [Joint Task Force] last week, including ongoing update of foundation entities (e.g. index terms, synonyms, extension codes, etc.) with

• annual updates for entities below the shoreline,

• a 5-year cycle for update of entities above the shoreline, and

• a 10-year cycles for updates to the rules.

and from the September 26, 2018 teleconference:

- WHO has updated the proposal platform to allow voting by CSAC* members and to align the process with the historical practices of the URC [ICD-10 Update and Revision Committee].

- 90 proposals have been identified from the platform for consideration by the CSAC this year, though not all of them can be reviewed in detail face-to-face during the WHO-FIC Network Annual Meeting 2018. A call may be held in advance to discuss some specific priorities.

- Given the huge volume of proposals, the meeting will go through the new procedures for the CSAC, review the voting process and tools, overview the proposal platform and how to use it, and determine timelines and workload for after the meeting.

- CSAC governance will also be presented together with the content of ICD-11 prior to submission of the report on ICD-11 to the WHO Governing Bodies for review by the WHO Executive Board [in January 2019]

Source: WHO-FIC Council Google platform: WHO-FIC Council Teleconferences

*The Classifications and Statistics Advisory Committee (CSAC) takes over the role of the ICD-10 Update and Revision Committee (URC). The last update for ICD-10 will be 2019.

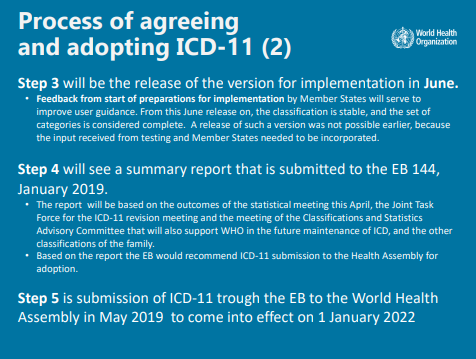

The ICD-11 MMS is expected to be frozen again in January 2019 in preparation for submission of the report to the Executive Board (EB):

Beyond World Health Assembly adoption, ICD-11 will be subject to an update and maintenance cycle:

(See Reference Guide Annex 3.7.1 – 3.7.6 for detailed information on ICD-11 Updating Cycles and Proposal Workflows.)

I’ve been unable to confirm whether the first update released after the June 2018 “Implementation” version would be a January 2019 release, or whether the June 2018 version is intended to remain more or less stable for a further year, until January 2020.

If WHO were to accept any of the proposals contained within my individual submissions and my joint submissions with Mary Dimmock, for example, approving our recommendations for deprecating the prefix “Benign”; deprecating Postviral fatigue syndrome as lead Concept Title; assigning separate Concept Title codes to Myalgic encephalomyelitis and to Chronic fatigue syndrome; or approving Exclusions under Bodily distress disorder (BDD), any approved recommendations would appear initially in the orange ICD-11 Maintenance Platform pending their eventual incorporation into an “Implementation” release.

I will keep you apprised of any significant developments.

References:

1 G93.3 Postviral fatigue syndrome, ICD-10 Browser Version: 2016. Accessed November 22, 2018

2 World Health Organization finally releases next edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) Dx Revision Watch, July 25, 2018

3 8E49 Postviral fatigue syndrome, ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (ICD-11 MMS) 2018 version for preparing implementation. Accessed November 22, 2018

4 8E49 Postviral fatigue syndrome, ICD-11 (Mortality and Morbidity Statistics) Maintenance Platform. Accessed November 22, 2018 The content made available on this platform is not a released version of the ICD-11. It is a work in progress in between released versions.

5 A proposal for the ICD-10 G93.3 legacy terms for ICD-11: Part Two. Dx Revision Watch, April 3, 2017

6 PDF: Proposal: Revision of G93.3 legacy terms for ICD-11, Dimmock & Chapman, March 27, 2017

7 Proposal: Revision of G93.3 legacy terms for ICD-11, Dr Tarun Dua, November 6, 2017

8 Response by Dimmock & Chapman to Dr Tarun Dua proposal of November 6, 2017, February 15, 2018

9 ICD-11 Reference Guide June 2018

10 Extract from Response to Dr Dua Proposal of November 6 2017: 4. Compliance with WHO standards and other considerations on relocation, Dimmock & Chapman, February 15, 2018