April 27, 2012

by meagenda

The six most essential questions in psychiatric diagnosis: a pluralogue: conceptual and definitional issues in psychiatric diagnosis, Parts 1 and 2

Post #161 Shortlink: http://wp.me/pKrrB-248

Below, I am posting the Abstract and Introduction to Parts 1 and 2 of Philos Ethics Humanit Med Review “The six most essential questions in psychiatric diagnosis: a pluralogue: conceptual and definitional issues in psychiatric diagnosis.”

Part 1 of this Review was published on January 13, 2012; Part 2 was published (as a provisional PDF) on April 18, 2012. I will post Part 3 when it becomes available.

Below Parts 1 and 2, I have posted the PDFs for Phillips J (ed): Symposium on DSM-5: Part 1. Bulletin of the Association for the Advancement of Philosophy and Psychiatry 2010, 17(1):1–26 and Phillips J (ed): Symposium on DSM-5: Part 2. Bulletin of the Association for the Advancement of Philosophy and Psychiatry 2010, 17(2):1–75 out of which grew the concept for the Philos Ethics Humanit Med Review Parts 1 and 2.

This is an interesting series of exchanges which expand on conceptual and definitional issues discussed in these two Bulletins but these are quite lengthy documents, 29 and 30 pp, respectively; PDFs are provided rather than full texts.

Review Part One

The six most essential questions in psychiatric diagnosis: a pluralogue part 1: conceptual and definitional issues in psychiatric diagnosis

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3305603/

Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2012; 7: 3.

Published online 2012 January 13. doi: 10.1186/1747-5341-7-3 PMCID: PMC3305603

Copyright ©2012 Phillips et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

Received August 15, 2011; Accepted January 13, 2012.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

The six most essential questions Part 1

The six most essential questions Part 1

or: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3305603/pdf/1747-5341-7-3.pdf

Html: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3305603/

or http://www.peh-med.com/content/7/1/3

James Phillips,

1

1 Allen Frances,

2 Michael A Cerullo,

3 John Chardavoyne,

1 Hannah S Decker,

4 Michael B First,

5 Nassir Ghaemi,

6 Gary Greenberg,

7 Andrew C Hinderliter,

8 Warren A Kinghorn,

2,9 Steven G LoBello,

10 Elliott B Martin,

1 Aaron L Mishara,

11 Joel Paris,

12 Joseph M Pierre,

13,14 Ronald W Pies,

6,15 Harold A Pincus,

5,16,17,18 Douglas Porter,

19 Claire Pouncey,

20 Michael A Schwartz,

21 Thomas Szasz,

15 Jerome C Wakefield,

22,23 G Scott Waterman,

24 Owen Whooley,

25 and Peter Zachar

10

1Department of Psychiatry, Yale School of Medicine, 300 George St., Suite 901, New Haven, CT 06511, USA

2Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, 508 Fulton St., Durham, NC 27710, USA

3Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience, University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, 260 Stetson Street, Suite 3200, Cincinnati, OH 45219, USA

4Department of History, University of Houston, 524 Agnes Arnold, Houston, 77204, USA

5Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Division of Clinical Phenomenology, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, NY 10032, USA

6Department of Psychiatry, Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington Street, Boston, MA 02111, USA

7Human Relations Counseling Service, 400 Bayonet Street Suite #202, New London, CT 06320, USA

8Department of Linguistics, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign 4080 Foreign Languages Building, 707 S Mathews Ave, Urbana, IL 61801, USA

9Duke Divinity School, Box 90968, Durham, NC 27708, USA

10Department of Psychology, Auburn University Montgomery, 7061 Senators Drive, Montgomery, AL 36117, USA

11Department of Clinical Psychology, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology, 325 North Wells Street, Chicago IL, 60654, USA

12Institute of Community and Family Psychiatry, SMBD-Jewish General Hospital, Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, 4333 cote Ste. Catherine, Montreal H3T1E4 Quebec, Canada

13Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, 760 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA

14VA West Los Angeles Healthcare Center, 11301 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90073, USA

15Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, 750 East Adams St., #343CWB, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA

16Irving Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, Columbia University Medical Center, 630 West 168th Street, New York, NY 10032, USA

17New York Presbyterian Hospital, 1051 Riverside Drive, Unit 09, New York, NY 10032, USA

18Rand Corporation, 1776 Main St Santa Monica, California 90401, USA

19Central City Behavioral Health Center, 2221 Philip Street, New Orleans, LA 70113, USA

20Center for Bioethics, University of Pennsylvania, 3401 Market Street, Suite 320 Philadelphia, PA 19104, USA

21Department of Psychiatry, Texas AMHSC College of Medicine, 4110 Guadalupe Street, Austin, Texas 78751, USA

22Silver School of Social Work, New York University, 1 Washington Square North, New York, NY 10003, USA

23Department of Psychiatry, NYU Langone Medical Center, 550 First Ave, New York, NY 10016, USA

24Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont College of Medicine, 89 Beaumont Avenue, Given Courtyard N104, Burlington, Vermont 05405, USA

25Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, 112 Paterson St., New Brunswick, NJ 08901, USA

Abstract

In face of the multiple controversies surrounding the DSM process in general and the development of DSM-5 in particular, we have organized a discussion around what we consider six essential questions in further work on the DSM. The six questions involve: 1) the nature of a mental disorder; 2) the definition of mental disorder; 3) the issue of whether, in the current state of psychiatric science, DSM-5 should assume a cautious, conservative posture or an assertive, transformative posture; 4) the role of pragmatic considerations in the construction of DSM-5; 5) the issue of utility of the DSM – whether DSM-III and IV have been designed more for clinicians or researchers, and how this conflict should be dealt with in the new manual; and 6) the possibility and advisability, given all the problems with DSM-III and IV, of designing a different diagnostic system. Part I of this article will take up the first two questions. With the first question, invited commentators express a range of opinion regarding the nature of psychiatric disorders, loosely divided into a realist position that the diagnostic categories represent real diseases that we can accurately name and know with our perceptual abilities, a middle, nominalist position that psychiatric disorders do exist in the real world but that our diagnostic categories are constructs that may or may not accurately represent the disorders out there, and finally a purely constructivist position that the diagnostic categories are simply constructs with no evidence of psychiatric disorders in the real world. The second question again offers a range of opinion as to how we should define a mental or psychiatric disorder, including the possibility that we should not try to formulate a definition. The general introduction, as well as the introductions and conclusions for the specific questions, are written by James Phillips, and the responses to commentaries are written by Allen Frances.

General Introduction

This article has its own history, which is worth recounting to provide the context of its composition.

As reviewed by Regier and colleagues [1], DSM-5 was in the planning stage since 1999, with a publication date initially planned for 2010 (now rescheduled to 2013). The early work was published as a volume of six white papers, A Research Agenda for DSM-V [2] in 2002. In 2006 David Kupfer was appointed Chairman, and Darrel Regier Vice-Chairman, of the DSM-5 Task Force. Other members of the Task Force were appointed in 2007, and members of the various Work Groups in 2008.

From the beginning of the planning process the architects of DSM-5 recognized a number of problems with DSM-III and DSM-IV that warranted attention in the new manual. These problems are now well known and have received much discussion, but I will quote the summary provided by Regier and colleagues:

Over the past 30 years, there has been a continuous testing of multiple hypotheses that are inherent in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, from the third edition (DSM-III) to the fourth (DSM-IV)… The expectation of Robins and Guze was that each clinical syndrome described in the Feighner criteria, RDC, and DSM-III would ultimately be validated by its separation from other disorders, common clinical course, genetic aggregation in families, and further differentiation by future laboratory tests–which would now include anatomical and functional imaging, molecular genetics, pathophysiological variations, and neuropsychological testing. To the original validators Kendler added differential response to treatment, which could include both pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions… However, as these criteria have been tested in multiple epidemiological, clinical, and genetic studies through slightly revised DSM-III-R and DSM-IV editions, the lack of clear separation of these syndromes became apparent from the high levels of comorbidity that were reported… In addition, treatment response became less specific as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were found to be effective for a wide range of anxiety, mood, and eating disorders and atypical antipsychotics received indications for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and treatment-resistant major depression. More recently, it was found that a majority of patients with entry diagnoses of major depression in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study had significant anxiety symptoms, and this subgroup had a more severe clinical course and was less responsive to available treatments… Likewise, we have come to understand that we are unlikely to find single gene underpinnings for most mental disorders, which are more likely to have polygenetic vulnerabilities interacting with epigenetic factors (that switch genes on and off) and environmental exposures to produce disorders. [[2], pp. 645-646]

As the work of the DSM-5 Task Force and Work Groups moved forward, a controversy developed that involved Robert Spitzer and Allen Frances, Chairmen respectively of the DSM-III and DSM-IV Task Forces. The controversy began with Spitzer’s Letter to the Editor, “DSM-V: Open and Transparent,” on July 18, 2008 in Psychiatric Times [3], detailing his unsuccessful effort to obtain minutes of the DSM-5 Task Force meetings. In ensuing months Allen Frances joined him in an exchange with members of the Task Force. In a series of articles and blog postings in Psychiatric Times, Frances (at times with Spitzer) carried out a sustained critique of the DSM-5 work in which he focused both on issues of transparency and issues of process and content [4-16]. The latter involved the Task Force and Work Group efforts to address the problems of DSM-IV with changes that, in Frances’ opinion, were premature and not backed by current scientific evidence. These changes included new diagnoses such as mixed anxiety-depression, an expanded list of addictive disorders, the addition of subthreshold conditions such as Psychosis Risk Syndrome, and overly inclusive criteria sets – all destined, in Frances’ judgment, to expand the population of the mentally ill, with the inevitable consequence of increasing the number of false positive diagnoses and the attendant consequence of exposing individuals unnecessarily to potent psychotropic medications. The changes also included extensive dimensional measures to be used with minimal scientific foundation.

Frances pointed out that the NIMH was embarked on a major effort to upgrade the scientific foundation of psychiatric disorders (described below by Michael First), and that pending the results of that research effort in the coming years, we should for now mostly stick with the existing descriptive, categorical system, in full awareness of all its limitations. In brief, he has argued, we are not ready for the “paradigm shift” hoped for in the 2002 A Research Agenda.

We should note that as the DSM-5 Work Groups were being developed, the Task Force rejected a proposal in 2008 to add a Conceptual Issues Work Group [17] – well before Spitzer and Frances began their online critiques.

In the course of this debate over DSM-5 I proposed to Allen in early 2010 that we use the pages of the Bulletin of the Association for the Advancement of Philosophy and Psychiatry (of which I am Editor) to expand and bring more voices into the discussion. This led to two issues of the Bulletin in 2010 devoted to conceptual issues in DSM-5 [18,19]. (Vol 17, No 1 of the AAPP Bulletin will be referred to as Bulletin 1, and Vol 17, No 2 will be referred to as Bulletin 2. Both are available at http://alien.dowling.edu/~cperring/aapp/bulletin.htm. webcite) Interest in this topic is reflected in the fact that the second Bulletin issue, with commentaries on Frances’ extended response in the first issue, and his responses to the commentaries, reached over 70,000 words.

Also in 2010, as Frances continued his critique through blog postings in Psychiatric Times, John Sadler and I began a series of regular, DSM-5 conceptual issues blogs in the same journal [20-33].

With the success of the Bulletin symposium, we approached the editor of PEHM, James Giordano, about using the pages of PEHM to continue the DSM-5 discussion under a different format, and with the goal of reaching a broader audience. The new format would be a series of “essential questions” for DSM-5, commentaries by a series of individuals (some of them commentators from the Bulletin issues, others making a first appearance in this article), and responses to the commentaries by Frances. Such is the origin of this article. (The general introduction, individual introductions, and conclusion are written by this author (JP), the responses by Allen Frances.

For this exercise we have distilled the wide-ranging discussions from the Bulletin issues into six questions, listed below with the format in which they were presented to commentators. (As explained below, the umpire metaphor in Question 1 is taken from Frances’ discussion in Bulletin 1.)…

Full document in PDF format

Review Part Two

(Note: Part Two was published on April 18, 2012 and addresses Questions 3 and 4. The complete article is available as a provisional PDF. The fully formatted PDF and HTML versions are in production. I will replace with the final version when available.)

The six most essential questions in psychiatric diagnosis: A pluralogue part 2: Issues of conservatism and pragmatism in psychiatric diagnosis

Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 2012, 7:8 doi:10.1186/1747-5341-7-8

http://www.peh-med.com/content/7/1/8/abstract

Published: 18 April 2012

The six most essential questions Part 2 Provisional

The six most essential questions Part 2 Provisional

The six most essential questions in psychiatric diagnosis: A pluralogue part 2: Issues of conservatism and pragmatism in psychiatric diagnosis

James Phillips, Allen Frances, Michael A Cerullo, John Chardavoyne, Hannah S Decker, Michael B First, Nassir Ghaemi, Gary Greenberg, Andrew C Hinderliter, Warren A Kinghorn, Steven G LoBello, Elliott B Martin, Aaron L Mishara, Joel Paris, Joseph M Pierre, Ronald W Pies, Harold A Pincus, Douglas Porter, Claire Pouncey, Michael A Schwartz, Thomas Szasz, Jerome C Wakefield, G Scott Waterman, Owen Whooley and Peter Zachar

Abstract (provisional)

In face of the multiple controversies surrounding the DSM process in general and the development of DSM-5 in particular, we have organized a discussion around what we consider six essential questions in further work on the DSM. The six questions involve: 1) the nature of a mental disorder; 2) the definition of mental disorder; 3) the issue of whether, in the current state of psychiatric science, DSM-5 should assume a cautious, conservative posture or an assertive, transformative posture; 4) the role of pragmatic considerations in the construction of DSM-5; 5) the issue of utility of the DSM – whether DSM-III and IV have been designed more for clinicians or researchers, and how this conflict should be dealt with in the new manual; and 6) the possibility and advisability, given all the problems with DSM-III and IV, of designing a different diagnostic system. Part I of this article took up the first two questions. Part II will take up the second two questions. Question 3 deals with the question as to whether DSM-V should assume a conservative or assertive posture in making changes from DSM-IV. That question in turn breaks down into discussion of diagnoses that depend on, and aim toward, empirical, scientific validation, and diagnoses that are more value-laden and less amenable to scientific validation. Question 4 takes up the role of pragmatic consideration in a psychiatric nosology, whether the purely empirical considerations need to be tempered by considerations of practical consequence. As in Part 1 of this article, the general introduction, as well as the introductions and conclusions for the specific questions, are written by James Phillips, and the responses to commentaries are written by Allen Frances.

The complete article is available as a provisional PDF. The fully formatted PDF and HTML versions are in production.

Symposium on DSM-5: Parts 1 and 2

Bulletin Vol 17 No 1

Bulletin Vol 17 No 1

Phillips J (ed): Symposium on DSM-5: Part 1. Bulletin of the Association for the

Advancement of Philosophy and Psychiatry 2010, 17(1):1–26

Bulletin Vol 17 No 2

Bulletin Vol 17 No 2

Phillips J (ed): Symposium on DSM-5: Part 2. Bulletin of the Association for the Advancement of Philosophy and Psychiatry 2010, 17(2):1–75

One focus for this site has been the monitoring of the various iterations towards the revision of the Somatoform Disorders categories of DSM-IV, for which radical reorganization of existing DSM categories and criteria is proposed.

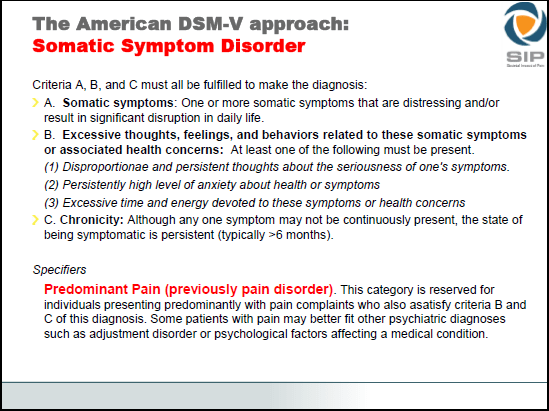

As the DSM-5 Development site documentation currently stands (April 27, 2012), the “Somatic Symptom Disorders” Work Group (Chaired by Joel E. Dimsdale, M.D.) proposes to rename Somatoform Disorders to “Somatic Symptom Disorders” and to fold a number of existing somatoform disorders together under a new rubric, which the Work Group proposes to call “Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder.”

Complex Somatic Symptom Disorder (CSSD) would include the previous DSM-IV diagnoses of somatization disorder [DSM IV code 300.81], undifferentiated somatoform disorder [DSM IV code 300.81], hypochondriasis [DSM IV code 300.7], as well as some presentations of pain disorder [DSM IV code 307].

There is a more recently proposed, Simple Somatic Symptom Disorder (SSSD), which requires symptom duration of just one month, as opposed to the six months required to meet the CSSD criteria. There is also an Illness Anxiety Disorder (hypochondriasis without somatic symptoms); and a proposal to rename Conversion Disorder to Functional Neurological Disorder and possibly locate under Dissociative Disorders.

There is some commentary on the Somatoform Disorders in DSM-IV in this discussion from Bulletin 1:

Bulletin Vol 17 No 1, Page 19:

Doing No Harm: The Case Against Conservatism

G. Scott Waterman, M.D. David P. Curley, Ph.D.

Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont College of Medicine

DSM-5 submission

1 Allen Frances,2 Michael A Cerullo,3 John Chardavoyne,1 Hannah S Decker,4 Michael B First,5 Nassir Ghaemi,6 Gary Greenberg,7 Andrew C Hinderliter,8 Warren A Kinghorn,2,9 Steven G LoBello,10 Elliott B Martin,1 Aaron L Mishara,11 Joel Paris,12 Joseph M Pierre,13,14 Ronald W Pies,6,15 Harold A Pincus,5,16,17,18 Douglas Porter,19 Claire Pouncey,20 Michael A Schwartz,21 Thomas Szasz,15 Jerome C Wakefield,22,23 G Scott Waterman,24 Owen Whooley,25 and Peter Zachar10

1 Allen Frances,2 Michael A Cerullo,3 John Chardavoyne,1 Hannah S Decker,4 Michael B First,5 Nassir Ghaemi,6 Gary Greenberg,7 Andrew C Hinderliter,8 Warren A Kinghorn,2,9 Steven G LoBello,10 Elliott B Martin,1 Aaron L Mishara,11 Joel Paris,12 Joseph M Pierre,13,14 Ronald W Pies,6,15 Harold A Pincus,5,16,17,18 Douglas Porter,19 Claire Pouncey,20 Michael A Schwartz,21 Thomas Szasz,15 Jerome C Wakefield,22,23 G Scott Waterman,24 Owen Whooley,25 and Peter Zachar10

Final day: Submissions to third DSM-5 stakeholder review

June 15, 2012 by meagenda

Final day: Submissions to third DSM-5 stakeholder review

Post #183 Shortlink: http://wp.me/pKrrB-2fn

The third and final stakeholder review is scheduled to close today, Friday, June 15.

I am collating copies of submissions on these pages.

A copy of my own comment is published below in text and PDF format. If you are unable to submit your own letter or short of time, please consider endorsing Mary Dimmock’s submission or one of the other submissions or one from last year with a note to say that although the criteria have been revised since last year, the underlying concerns remain.

Continued on Page 2

Share this:

Filed under American Psychiatric Association (APA), DSM revision process, DSM-5 draft proposals, DSM-5 field trials, DSM-5 third draft, Functional Somatic Syndrome (FSS), Kappa, MUS, Somatic Symptom Disorder, Somatoform Disorders Tagged with american psychiatric association, criticism of dsm-5, dsm-5 development, dsm-5 stakeholder review, field trials, public comment, reliability and prevalance, somatic symptom disorders, somatoform disorders, suzy chapman