Briefing paper on ICD-11 and PVFS, ME and CFS: Part 2

September 30, 2014

Post #316 Shortlink: http://wp.me/pKrrB-41q

Update: With regard to a new parent class: Functional clinical forms of the nervous system proposed for inclusion within the ICD-11 Diseases of the nervous system (Neurology) chapter, see Stone et al paper:

Functional disorders in the Neurology section of ICD-11: A landmark opportunity

Jon Stone, FRCP, Mark Hallett, MD, Alan Carson, FRCPsych, Donna Bergen, MD and Raad Shakir, FRCP

Neurology December 9, 2014 vol. 83 no. 24 2299-2301

doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001063

Full free text:

http://www.neurology.org/content/83/24/2299.long

Full free PDF:

http://www.neurology.org/content/83/24/2299.full.pdf+html

As previously posted:

Part two of a three part report on the status of ICD-11 proposals for the classification of the three ICD-10 entities:

G93.3 Postviral fatigue syndrome (coded under parent class G93 in Tabular List)

Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis (inclusion term to G93.3 in Tabular List)

Chronic fatigue syndrome (indexed to G93.3 in Volume 3: Alphabetical Index)

Part 1: Status of the ICD-11 development process published September 29, 2014

Part 2: Status of proposals for the classification of PVFS, BME, and CFS in the public version of the ICD-11 Beta drafting platform

Seven years into the development process and it’s still not known how ICD-11 intends to classify the three G93.3 terms.

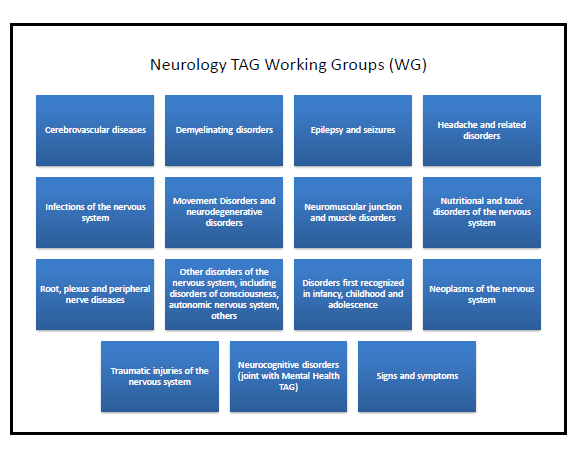

Sub working groups were formed under TAG Neurology with responsibility for the restructured disease and disorder blocks proposed for ICD-11’s Diseases of the nervous system chapter.

It hasn’t been established which of the various sub working groups has responsibility for making recommendations for the revision of the G93.3 terms or who the members of the subgroup(s) and its external advisers are.

Neurology Topic Advisory Group (TAG) sub working groups:

Source: Slide #16: Summary of progress, Neurology Advisory Group, Raad Shakir (Chair): http://www.hc2013.bcs.org/presentations/s1d_thu_1530_Shakir_amended.ppt

No journal papers, editorials, presentations or public domain progress reports have been published, to date, on behalf of TAG Neurology that discuss emerging proposals or intentions for the classification of the three G93.3 terms for ICD-11.

The public version of the Beta drafting platform displays no editing change histories or category notes. Until the three terms have been restored to the Beta draft the public is reliant on what information WHO/ICD Revision chooses to disclose, which thus far, has been minimal.

Currently, there is no information within the Beta draft for proposals for these three terms. The continued absence of these terms from the draft (now missing for over 18 months) is hampering professional and public stakeholder scrutiny, discourse and comment.

This is not acceptable for any disease category given that ICD Revision is being promoted by WHO’s, Bedirhan Üstün, as an open and transparent process and inclusive of stakeholders.

This next section summarizes the most significant changes since May 2010 for several iterations of the Neurology chapter, during the Alpha and Beta drafting phases, as displayed in the public version of the draft.

Tracking the progression of the G93.3 terms through the Alpha and Beta drafting stages

In May 2010: the ICD-10 G93 legacy parent class: Other disorders of brain was retired and a change in hierarchy for class Postviral fatigue syndrome recorded. See Notes Tree screenshot [12].

A Definition was inserted for Chronic fatigue syndrome. See Change history screenshot [13].

Chronic fatigue syndrome replaced Postviral fatigue syndrome as the new ICD Title term and now sat directly under parent class: Other disorders of the nervous system.

Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis was specified as an Inclusion term under Synonyms to new ICD Title term: Chronic fatigue syndrome. See Alpha draft screenshot [14].

Postviral fatigue syndrome was at that point unaccounted for in the Alpha draft.

By July 2012: 13 additional terms were now listed under Synonyms, including Postviral fatigue syndrome, and two terms imported from the yet to be implemented, ICD-10-CM (the ICD-10-CM Chapter 18 R53.82 codes: chronic fatigue syndrome nos and chronic fatigue, unspecified).

The Definition field was now blanked.

At this point, ICD Title term: Chronic fatigue syndrome was no longer displaying as a child category directly under parent class: Other disorders of the nervous system.

The listing for Chronic fatigue syndrome now appeared under a new “Selected Cause” subset, which displayed as a sub linearization within the Foundation Component. The purpose of this subset, which aggregated many terms from Neurology and other chapters, was not evident from the Beta draft.

By November 2012: ICD Revision had re-inserted a scrappy, revised Definition for Chronic fatigue syndrome. I have sourced this draft definition to an internal ICD Revision/Stanford Protege document (line 1983):

Chronic fatigue syndrome is characterized by extreme chronic fatigue of an indeterminate cause, which is disabling andt [sic] does not improve with rest and that is exacerbated by physical or mental activity.

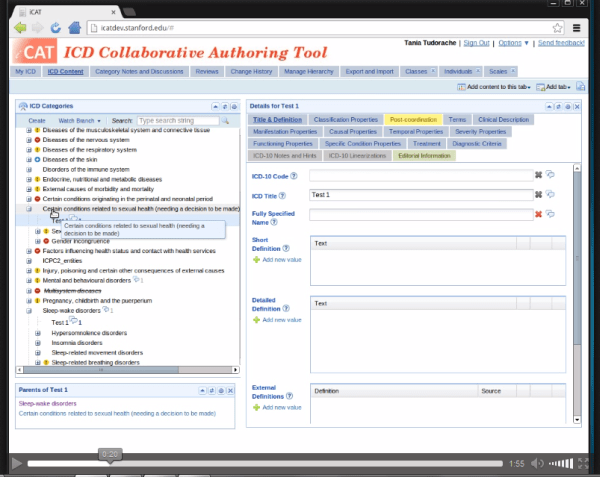

Below is a screenshot from the Beta draft taken in July 2012, before a Definition for Title term, Chronic fatigue syndrome had been re-inserted.

(It isn’t evident in the screenshot, but the asterisk at the end of Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis displayed a hover text denoting its specification as the Inclusion term to ICD Title term, Chronic fatigue syndrome. Also not evident in this cropped screenshot is the listing of Postviral fatigue syndrome under Synonyms.)

Source: ICD-11 Beta drafting platform, July 25, 2012.

This “Selected Cause” sub linearization was later removed from the public Beta draft and some of the terms that had been listed under it were restored to the Neurology chapter and to other chapters. But ICD Title term, Chronic fatigue syndrome, its Inclusion term and list of Synonyms were not restored to any chapter.

Since February 2013: no listing can be found in any chapter of the public version of the Beta draft, under any linearization, for any of the terms, Postviral fatigue syndrome, Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis or Chronic fatigue syndrome, as uniquely coded ICD Title terms, or as Inclusion terms or Synonyms to Title terms, or in the ICD-11 Beta Index.

Since June 2013: My repeated requests for an explanation for the absence of these three terms from the Beta draft and for ICD Revision’s intentions for these terms were ignored by ICD Revision until July 2014, when a response was forthcoming from ICD Revision’s, Dr Geoffrey Reed.

(It is understood that Annette Brooke MP also received a response, in July, from WHO’s, Dr Robert Jakob, in respect of the joint organizations’ letter of March 18, for which Ms Brooke had been a co-signatory.)

What clarifications have been given?

Feb 12, 2014: An unidentified admin for the @WHO Twitter account replied to a member of the public: “Fibromyalgia, ME/CFS are not included as Mental & Behavioural Disorders in ICD-10, there is no proposal to do so for ICD-11.” A similar affirmation was tweeted by Gregory Hartl, head of public relations/social media, WHO.

July 24, 2014: Geoffrey Reed PhD (Senior Project Manager for revision of Mental and behavioural disorders) replied to Suzy Chapman, by email:

Dr Reed stated inter alia that the placement of ME and related conditions within the broader classification is still unresolved.

That he had no influence or control over this process; his authority being limited to coordinating recommendations related to conditions that should or should not be placed in the chapter on Mental and behavioural disorders.

That there has been no proposal and no intention to include ME or other conditions such as fibromyalgia* or chronic fatigue syndrome in the classification of mental disorders.

That the easiest way to make this absolutely clear will be through the use of exclusion terms. However, he would be unable to ask that exclusion terms are added to relevant Mental and behavioural disorders categories (e.g. Bodily Distress Disorder) until the conditions that are being excluded exist in the classification. That at such time, he would be happy to do that.

That since his purview does not extend to the section on classification of Diseases of the nervous system or other areas outside the Mental and behavioural disorders chapter, he was unable to provide any information related to how these conditions will be classified in other chapters.

That he was unable to comment about the management of correspondence by other TAG groups and signposted me to Dr Robert Jakob [the senior classification expert who had been copied into the joint organizations’ letter to WHO/ICD Revision, in March] whose role relates to the overall coordination of the classification.

*Fibromyalgia remains classified under ICD-11 Beta draft public version chapter “Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue” under parent: Certain specified soft tissue disorders, not elsewhere classified.

Irritable bowel syndrome remains classified under ICD-11 Beta draft public version chapter “Diseases of the digestive system” under: Functional gastrointestinal disorders > Irritable bowel syndrome and certain specified functional bowel disorders.

In August, I submitted two FOI requests, one to the Scottish Health Directorate, one to the English Department of Health. The latter was not deemed specific enough in terms of named health agencies for a response to be generated and will require resubmission.

September 24, 2014: FOI request fulfilled by (SCOTLAND) ACT 2002 (FOISA), received from David Cline, Unit Head, Strategic Planning and Clinical Priorities Team, by email:

The Quality Unit: Health and Social Care Directorates

Planning & Quality Division[Addresses redacted]

Your ref: FoI/14/01460

24 September 2014

REQUEST UNDER THE FREEDOM OF INFORMATION (SCOTLAND) ACT 2002 (FOISA)

Thank you for your request dated 27 August 2014 under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002 (FOISA)…

Your request

Under the Freedom of Information (Scotland) Act 2002, please provide the following.

Please send me copies of all correspondence, emails, letters, minutes relating to:

Enquiries made by Scottish Health Directorate to World Health Organization (WHO), 20 Av Appia, CH-1211, Geneva, in respect of:

Classification of the three ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases 10th edition) G93.3 coded disease terms in the forthcoming revision of ICD-10, to be known as ICD-11:

Postviral fatigue syndrome (Post viral fatigue syndrome; PVFS)

Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis (myalgic encephalomyelitis; myalgic encephalitis; ME);

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS; CFS/ME, ME/CFS)

During the period:

1] January 1, 2013 – December 31, 2013

2] January 1, 2014 – July 31, 2014

I also request copies of responses received from WHO in reply to enquiries made by Scottish Health Directorate during these periods in respect of the above ICD disease categories.

Response to your request

Information held covering the time period indicated relates to an email exchange on 11 and 12 March 2014 as part of a request for advice in answering Ministerial correspondence.

On 11 March the World Health Organisation WHO were asked “I would be very grateful for your help in confirming the status of an element within the WHO’s ICD 11 regarding ME/CFS. On 25th February in the UK parliament, the Under-Secretary of State for Health informed the UK parliament that the WHO had publicy stated that there was no proposal to reclassify ME/CFS in ICD-11…I would be very grateful if you can confirm that this is the case and if possible, provide a web link to the original wording so I can include this within the correspondence I am preparing”.

The WHO responded on 12 March; “The question regarding MS/CFS [sic] and ICD-11 has been asked recently by several different parties. At this point in time, the ICD-11 is still under development, and to handle this classification issue we will need more time and input from the relevant working groups. It would be premature to make any statement on the subject below.

The general information on ICD Revision can be accessed here: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/revision/. The current state of development of ICD-11 (draft) can be viewed here (and comments can be made, after self registration): http://www.who.int/classifications/icd11 ”.

A further email on 12 March to the WHO asked; “It would be fair to say then …that work will continue on the draft with an expected publication in 2015?”.

WHO responded on 12 March; “Work on the draft will continue until presentation at the World Health Assembly in 2017. Before, reviews and field testing will provide input to a version that is available for commenting, as much as possible and proposals can be submitted online* with the mechanisms provided already.”

*Since the three terms are currently not accounted for within the Beta draft this impedes the submission of comments.

This is the sum total of what has been disclosed by WHO/ICD Revision in respect of current proposals for the classification of the three ICD-10 G93.3 terms, despite the fact that ICD-11 has now been under development for 7 years, and prior to the timeline extension in January 2014, the new edition had been scheduled for WHA approval and dissemination in 2015.

What might the working group potentially be considering?

- The terms may have been removed from the draft in order to mitigate controversy over a proposed change of chapter location, change of parent class, reorganization of the hierarchy, or over the wording of Definition(s). (Whether a term is listed as a coded Title term, or is specified as an Inclusion term to a coded term or listed under Synonyms to a coded term, dictates which of the terms is assigned a Definition. If, for example, CFS and [B]ME were both coded as discrete ICD Title terms, both terms will require the assigning of Definitions and other Content Model descriptors.)

- TAG Neurology may be proposing to retain all three terms under the Neurology chapter, under an existing parent class that is still under reorganization, and has taken the three terms out of the linearizations in the meantime, or is proposing to locate one or more of the terms under a new parent class for which a name and location has yet to be agreed.

- TAG Neurology may be proposing to locate one or more of these terms under more than one chapter, for example, under the Neurology chapter but dual parented under the Symptoms and signs chapter. Or multi parented and viewable under a multisystem linearization, if the potential for a multisystem linearization remains under discussion.

- TAG Neurology may be proposing to retire one or more of these three terms (despite earlier assurances by senior WHO classification experts) but I think this unlikely. ICD-11 will be integrable with SNOMED CT, which includes all three terms, albeit with ME and BME listed as synonyms to coded CFS, with PVFS assigned a discrete SNOMED CT code.

- Given the extension to the timeline, TAG Neurology may be reluctant to make decisions at this point because it has been made aware of the HHS contract with U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM) to develop “evidence-based clinical diagnostic criteria for ME/CFS” and to “recommend whether new terminology for ME/CFS should be adopted.” Any new resulting criteria or terminology might potentially be used to inform ICD-11 decisions.

Other possibilities might be listing one or more of these terms under parent class, Certain specified disorders of the nervous system or under Symptoms, signs and clinical findings involving the nervous system, which is dual parented under both the Neurology chapter and the Symptoms and signs chapter.

All currently listed parent and child categories within the Neurology chapter can be viewed here:

Click on the small grey arrows next to Beta draft categories to display their parent, child and grandchildren categories, as drop down hierarchies.

Select this coloured button to display symbols and hover text indicating which linearization(s) a selected term is listed under.

Select this coloured button to display symbols and hover text indicating which linearization(s) a selected term is listed under.

http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd11/browse/f/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/1296093776

There is a new parent class proposed for the ICD-11 Neurology chapter called, Functional clinical forms of the nervous system, which Dr Jon Stone has been working on [15] [17].

Under this new Neurology chapter parent class, it is proposed to relocate or dual locate a list of “functional disorders” (Functional paralysis or weakness; Functional sensory disorder; Functional movement disorder; Functional gait disorder; Functional cognitive disorder etc.) which in ICD-10 are classified under the Chapter V Dissociative [conversion] disorders section.

The rationale for this proposed chapter shift for Conversion disorders/functional disorders is beyond the scope of this briefing paper.

In a 2013 editorial, Prof Raad Shakir (Chair, TAG Neurology) briefly discusses the proposed reorganization of what he calls the “rag bag of diverse and disparate diseases” that is parent class, Other disorders of the nervous system [16].

He writes, “In addition, there will also be a section on Functional disorders of the nervous system, reflecting the growing diagnostic importance of such syndromes.”

It’s not clear whether this reference, in 2013, to the inclusion of a new section for “Functional disorders of the nervous system” within the Neurology chapter relates to the relocation or dual location of those “functional disorders” currently classified under Dissociative [conversion] disorders within ICD-10 Chapter V, or whether Prof Shakir was referring to potential inclusion within the Neurology chapter of a section for “Functional somatic syndromes.” But I consider the former more likely.

There is currently no inclusion within any chapter for a specific parent class for “Functional somatic syndromes,” or “Functional somatic disorders” or “interface disorders” under which, conceivably, those who consider CFS, ME, IBS and FM to be “speciality driven” manifestations of a similar underlying functional disorder might be keen to see these terms aggregated.

I shall return to the subject of “interface disorders” in Part 3.

There remain 6 important questions to be answered:

• under which chapter(s) are PVFS, BME and CFS proposed to be located?

• under which parent classes?

• what hierarchies are proposed, in terms of coded Title terms, Inclusions, Synonyms?

• which of the terms are to be assigned definitions?

• where will definitions be sourced from?

• when will the terms be restored to the draft to enable scrutiny and comment?

Extract, ICD-11 document Known Concerns and Criticisms:

“It may be true that some advocacy groups may give inputs in line with their vested interests or object to the listings in ICD-11 Beta. When such public controversy occurs, it is better to have it in an open and transparent discussion…”

Having obscured these terms from the Beta drafting platform eighteen months ago, with no explanation, ICD Revision Steering Group and TAG Neurology, which are both accountable to WHO, have disenfranchised professional and advocacy stakeholders from scrutiny of, and participation in what is being touted as an open and transparent process.

For Part 1 of this briefing document: Part 1: Status of the ICD-11 development process

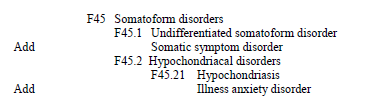

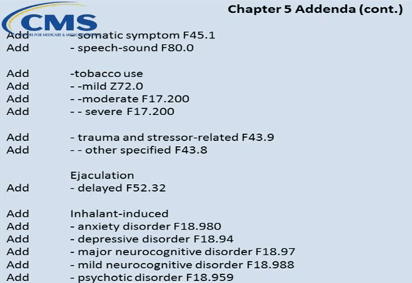

In Part 3, I shall be setting out what is currently known about the status of proposals for the revision of ICD-10’s Somatoform disorders for the core and primary care versions of ICD-11.

Important caveats: The public Beta platform is not a static document, it is a work in progress, subject to daily editing and revision, to field test evaluation and to approval by the RSG and WHO classification experts. Not all new proposals may survive the ICD-11 field tests. Chapter numbering, codes and “sorting codes” currently assigned to ICD categories are not stable and will change as chapters and parent/child hierarchies are reorganized. The public version of the Beta is incomplete; not all “Content Model” parameters display or are populated; the draft may contain errors and omissions.

References for Part 2

12 https://dxrevisionwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/2icatnotegj92cfs.png

13 https://dxrevisionwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/change-history-gj92-cfs.png

14 https://dxrevisionwatch.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/icd11-alpha1-17-05-11.png

16 Shakir R, Rajakulendran, S. The 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) The Neurological Perspective JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(11):1353-1354. http://archneur.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1733323

17 Functional neurological disorders: The neurological assessment as treatment. Stone J. Neurophysiol Clin. 2014 Oct;44(4):363-73 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25306077