Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines (CDDG) for ICD‐11 Mental, Behavioural and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

June 28, 2019

Post #354 Shortlink: https://wp.me/pKrrB-4IQ

The ICD-10 “Blue Book” and “Green Book”

In the World Health Organization’s ICD-10 Tabular List there are no disease or disorder descriptions, criteria or diagnostic guidelines in any chapters other than the brief description texts for disorders coded within Chapter V Mental and behavioural disorders.

The WHO describes these brief description texts as suitable for use by coders or clerical workers and to serve as a reference point for compatibility with other classifications. These brief texts are not recommended for use by mental health professionals.

Two companion publications were developed for use with ICD-10’s Chapter V which expand on these brief texts and provide clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. These publications are available as license free downloads:

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines (aka the “Blue Book”) intended for mental health professionals for general clinical, educational and service use:

The ICD-10 Diagnostic criteria for research (aka the “Green Book”) produced for research purposes and designed to be used in conjunction with the Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines “Blue Book”:

A survey of nearly 5,000 psychiatrists in 44 countries sponsored by the WHO and the World Psychiatric Association found that 70% of respondents mostly used the ICD-10 classification system in their daily clinical work compared to 23% of practitioners primarily using the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-IV [1].

ICD-11 and the CDDG

For ICD-11, the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse has developed the “Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines (CDDG) for ICD‐11 Mental, Behavioural and Neurodevelopmental Disorders.”

The CDDG provides expanded clinical descriptions, essential (required) features, boundaries with other disorders and normality, differential diagnoses, additional features, culture-related features and codes for all mental and behavioural disorders commonly encountered in clinical psychiatry; it is intended for mental health professionals and for general clinical, educational and service use.

The CDDG does not provide diagnostic criteria. The essential features are less rigid than DSM-5’s criteria sets and allow practitioners more flexibility to use clinical discretion when making a diagnosis.

CDDG review process

The CDDG review process has been undertaken via the Global Clinical Practice Network.

Qualified clinicians who signed up to participate in the CDDG guideline review process have been able to review and provide feedback on the draft content. No draft texts have been made available for public stakeholder scrutiny and comment and I have not had access, for example, to the most recent draft for the clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines for ICD-11’s Bodily distress disorder.

This paper in the February 2019 edition of World Psychiatry (Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders) describes major changes to the structure of the ICD‐11 classification of mental disorders as compared to ICD‐10; discusses new categories added for ICD‐11 and presents rationales for their inclusion; and describes important changes that have been made in each ICD‐11 disorder grouping [2].

What the paper does not give is a firm release date for the CDDG — stating only that the WHO will publish the CDDG as soon as possible following approval of the overall system by the World Health Assembly (WHA).

Member states approved the draft resolution to adopt ICD-11 at the 72nd World Health Assembly, in May 2019. Endorsement takes effect from January 01, 2022, which is the earliest date from which member states can begin reporting data using the new ICD-11 code sets.

Extract from Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders:

Disorders of bodily distress and bodily experience

ICD‐11 disorders of bodily distress and bodily experience encompass two disorders: bodily distress disorder and body integrity dysphoria. ICD‐11 bodily distress disorder replaces ICD‐10 somatoform disorders and also includes the concept of ICD‐10 neurasthenia. ICD‐10 hypochondriasis is not included and instead is reassigned to the OCRD [Ed: Obsessive‐compulsive and related disorders] grouping.

Bodily distress disorder is characterized by the presence of bodily symptoms that are distressing to the individual and an excessive attention directed toward the symptoms, which may be manifest by repeated contact with health care providers69. The disorder is conceptualized as existing on a continuum of severity and can be qualified accordingly (mild, moderate or severe) depending on the impact on functioning. Importantly, bodily distress disorder is defined according to the presence of essential features, such as distress and excessive thoughts and behaviours, rather than on the basis of absent medical explanations for bothersome symptoms, as in ICD‐10 somatoform disorders.

*Embedded links to the ICD-11 Orange Maintenance Platform disorder descriptions are not included in the paper.

DSM-5’s Somatic symptom disorder is listed under Synonyms to ICD-11’s Bodily distress disorder and indexed to 6C20.Z Bodily distress disorder, unspecified.

The CDDG is expected to be published as a licence free download. When the WHO has released the CDDG, I will update this post.

This Letter to the Editor published in the June 2019 edition of World Psychiatry (Public stakeholders’ comments on ICD-11 chapters related to mental and sexual health) summarizes common themes of the submissions for the mental disorder categories that generated the greatest response [3].

Extract:

A majority of submissions regarding bodily distress disorder were critical, but were often made by the same individuals (N=8). Criticism mainly focused on conceptualization (48%; κ=0.64) and the disorder name (43%; κ=0.91). Use of a diagnostic term that is closely associated with the differently conceptualized bodily distress syndrome5 was seen as problematic. One criticism was that the definition relies too heavily on the subjective clinical decision that patients’ attention directed towards bodily symptoms is “excessive”. A number of comments (17%; κ=0.62) expressed concern that this would lead to patients being classified as mentally disordered and preclude them from receiving appropriate biologically-oriented care. Some contributors submitted proposals for changes to the definition (30%; κ=0.89). Others opposed inclusion of the disorder altogether (26%; κ=0.88), while no submission (κ=1) expressed support for inclusion. The WHO decided to retain bodily distress disorder as a diagnostic category6 and addressed concerns by requiring in the CDDG the presence of additional features, such as significant functional impairment.

Note: “Use of a diagnostic term that is closely associated with the differently conceptualized bodily distress syndrome5 was seen as problematic.”

Whilst it is welcomed that this specific concern has been acknowledged within this Letter to the Editor, I have drawn to the authors’ attention that WHO/ICD Revision has repeatedly failed to respond to requests to provide a rationale for its re-purposing of a diagnostic term that is already strongly associated with the Fink et al (2010) Bodily distress syndrome*, despite provision of examples from the literature clearly demonstrating that these two terms have been used interchangeably by researchers and practitioners, since 2007 [4].

The potential for confusion and conflation of these differently conceptualized disorder constructs was acknowledged by the WHO’s Dr Geoffrey Reed, in 2015. However, there has been no discussion of this potential in any of the S3DWG working group’s progress reports and field trial evaluations. If the WHO is not willing to reconsider and remedy this problem, there is the expectation that a rationale for going forward with the Bodily distress disorder term is provided for clinical and public stakeholders.

*Operationalized in Denmark and beyond, BDS is differently conceptualized to ICD-11’s BDD diagnostic construct: BDS has very different criteria/essential features, based on physical symptom patterns or clusters from organ systems; psychobehavioural responses to symptoms do not form part of the BDS criteria; BDS requires the symptoms to be “medically unexplained”; is inclusive of a different patient population to ICD-11’s BDD, and crucially, is considered by its authors to capture myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, IBS and fibromyalgia patients under a single, unifying BDS diagnosis.

As an unprocessed proposal is currently under review with the CSAC/MSAC committees I have requested that earlier submissions, which were marked as rejected in February 2019 with no adequate rationale for dismissing the concerns raised within them, are reconsidered and that the WHO responds to three specific concerns:

a) its re-purposing of a disorder term already in use interchangeably for a differently conceptualized disorder construct;

b) the potential difficulties of maintaining disorder construct integrity within and beyond ICD-11 and the implications for clinical utility, data reporting and statistical analysis;

c) the requirement for adding exclusions under BDD for Concept Title 8E49 Postviral fatigue syndrome and its inclusion terms, to mitigate confusion/conflation with the Fink et al (2007, 2010) Bodily distress syndrome.

Bodily distress disorder in SNOMED CT

The SNOMED CT Concept term SCTID: 723916001: Bodily distress disorder was added to the July 2017 release of the SNOMED CT International Edition.

SNOMED International’s classification leads confirmed that the term had been added by the team working on the SNOMED CT and ICD-11 MMS Mapping Project as “an exact match for the ICD-11 term, Bodily distress disorder.”

In ICD-11, Bodily distress disorder has specifiers for three degrees of severity: Mild BDD; Moderate BDD; and Severe BDD, which are each assigned a unique code and a discrete description/characterization text.

It was submitted that including the three ICD-11 BDD severities might help clinicians and coders distinguish between the SNOMED CT/ICD-11 Bodily distress disorder concept term and the similarly named, but differently conceptualized, Bodily distress syndrome (Fink et al 2010), which has two severities.

A request for addition of the three BDD severities was submitted and approved in early 2018 and Mild BDD; Moderate BDD; and Severe BDD were added as three discretely coded for Children concepts for the July 2018 release of the International Edition and subsequently absorbed into the various national editions.

ICD-11 PHC

The ICD-11 CDDG should not be confused with the ICD-11 PHC.

Since 2012, I have been reporting on the parallel development of the ICD-11 Primary Health Care (PHC) Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Mental Disorders (ICD-11 PHC).

The ICD-11 PHC is a revision of the Diagnostic and Management Guidelines for Mental Disorders in Primary Care: ICD-10 Chapter V Primary Care Version. 1996.

ICD-11 PHC is a clinical tool written in simpler language to assist non-mental health specialists in primary care settings and non medically trained health workers, and also intended for use in low resource settings and in low- to middle-income countries.

It comprises 27 mental disorders considered to be most clinically relevant in primary care and low resource settings. (It is a misnomer to refer to the ICD-11 PHC as the “Primary Care version of ICD-11” since it contains just 27 mental disorders and no general medical diseases or conditions.)

It is important to note that like the ICD-10 PHC, this revised diagnostic and management guideline won’t be mandatory for use by member states, although the WHO hopes this revised edition will have greater clinical utility than the ICD-10 PHC (1996).

The WHO intends to make the ICD-11 PHC publication, once completed, free to download by anyone. There is currently no date available for its projected finalization or release.

The revision is the responsibility of the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse advised by an external advisory group — the Primary Care Consultation Group (PCCG) which is chaired by Prof Sir David Goldberg*; Vice-chairs: Dr Michael Klinkman and WHO’s, Dr Geoffrey Reed.

*Prof Sir David Goldberg also chaired the working group for the development of ICD-10 PHC (1996). Dr Michael Klinkman is a GP who represents WONCA (World Organization of Family Doctors) and current convenor of WONCA’s International Classification Committee (WICC) that is responsible for the development and update of the WHO endorsed, ICPC-2 (International Classification of Primary Care).

The full draft texts for the 27 mental disorder categories proposed for inclusion in the ICD-11 PHC have not been made available for public scrutiny, but a number of progress papers, field trial evaluations and presentations have been published since 2010 [5-8].

25 of the 27 mental disorder categories proposed for inclusion in the ICD-11 PHC have equivalence with mental disorder classes within the core ICD-11’s Chapter 06.

ICD-11 PHC is proposed to include a disorder category called “Bodily stress syndrome (BSS)” which replaces ICD-10 PHC’s “F45 Unexplained somatic complaints/medically unexplained symptoms” and “F48 Neurasthenia” categories.

This proposed “Bodily stress syndrome (BSS)” diagnosis has been adapted from the Fink et al (2010) Bodily distress syndrome (BDS). “Bodily stress syndrome (BSS)” does not have direct equivalence to a diagnostic construct in the core ICD-11.

The ICD-11 PHC’s “Bodily stress syndrome (BSS)” requires at least 3 persistent, medically unexplained symptoms, over time, of cardio-respiratory, gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, or general symptoms of tiredness and exhaustion, that result in significant distress or impairment.

Under exclusions and differential diagnoses for BSS, certain psychiatric and general medical diagnoses have to be excluded but CFS, ME; IBS; and FM appear not to be specified as exclusions. So this (non mandatory) 27 mental disorder guideline needs very close scrutiny.

For the mandatory core ICD-11 classification, the WHO is going forward with the differently conceptualized, Bodily distress disorder (BDD), which has close alignment with DSM-5’s Somatic symptom disorder.*

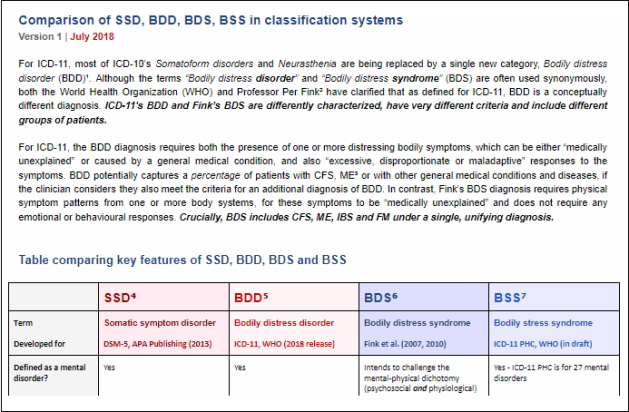

*See: Comparison of SSD, BDD, BDS, BSS in classification systems, Chapman & Dimmock, July 2018.

If ICD-11 PHC goes forward with its proposed BSS category, there will be all these diagnostic constructs in play:

Somatic symptom disorder (DSM-5; under Synonyms to BDD in the core ICD-11)

Bodily distress disorder (core ICD-11; SNOMED CT)

Bodily stress syndrome (ICD-11 PHC guideline for 27 mental disorders)

Bodily distress syndrome (Fink et al 2010, operationalized in Denmark and beyond)plus the existing ICD-10 and SNOMED CT Somatoform disorders categories and their equivalents in ICPC-2.

References:

1 Reed GM, Correia J, Esparza P, Saxena S, Maj M (2011). The WPA-WHO global survey of psychiatrists’ attitudes towards mental disorders classification. World Psychiatry, 10, 118–131. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00034.x

2 Reed GM, First MB, Kogan CS, et al. Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. World Psychiatry, 2019;18(1):3–19. doi:10.1002/wps.20611

Html: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6313247/

PDF: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6313247/pdf/WPS-18-3.pdf

3 Fuss J, Lemay K, Stein DJ, Briken P, Jakob R, Reed GM and Kogan CS. (2019). Public stakeholders’ comments on ICD‐11 chapters related to mental and sexual health. World Psychiatry, 18: 233-235. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/wps.20635

4 Chapman S. Proposal and rationale for Deletion of the Entity Bodily distress disorder. Proposal submitted via ICD-11 Beta draft Proposal Mechanism, March 02, 2017.

5 T P Lam, D P Goldberg, A C Dowell, S Fortes, J K Mbatia, F A Minhas, M S Klinkman. Proposed new diagnoses of anxious depression and bodily stress syndrome in ICD-11-PHC: an international focus group study, Family Practice, Volume 30, Issue 1, February 2013, Pages 76–87, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cms037

6 MASTER PROTOCOL Depression, Anxiety and Somatic Symptoms in Global Primary Care Settings: A Field Study for the ICD-11-PHC Version 2 for WHO Research Ethics Review Committee.

Click to access WorldHealth14.pdf

7 Fortes, Sandra, Ziebold, Carolina, Reed, Geoffrey M, Robles-Garcia, Rebeca, Campos, Monica R, Reisdorfer, Emilene, Prado, Ricardo, Goldberg, David, Gask, Linda, & Mari, Jair J.. (2019). Studying ICD-11 Primary Health Care bodily stress syndrome in Brazil: do many functional disorders represent just one syndrome? Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 41(1), 15-21. Epub October 11, 2018.

Html: https://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0003

PDF: http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rbp/v41n1/1516-4446-rbp-1516444620180003.pdf

8 Presentation: Rosendale, M (2017). MUS becomes Bodily Stress Syndrome in the ICD-11 for primary care

Resources:

Comparison of Classification and Terminology Systems, Chapman & Dimmock, July 2018

Comparison of SSD, BDD, BDS, BSS in classification systems, Chapman & Dimmock, July 2018